Our feature OKI Wanna Know is your opportunity to better understand your community and its history. This week, we go back to the Cincinnati of 100 years ago.

Jeff wrote in saying he noticed a large monument, tucked away in a corner of Eden Park. It's dedicated to Battery F of the 136th Field Artillery. Jeff says he's curious about the unit's history, but couldn't find anything beyond the names on the plaque.

Battery F of the 136th Field Artillery originally started as a cavalry unit of the Ohio National Guard. Many of its members served along the border with Mexico before the United States entered the First World War.

Sergeant First Class Joshua Mann is the historian for the Ohio National Guard. He says the state was having trouble getting enough men to make up an all-Ohio division.

"The state of Ohio leadership went to the cavalry squadron and said, 'Look, there is no use for cavalry in the trenches of France. They're not using them. The French aren't using them. The Germans aren't using them. The British aren't using them," he says. "If you want to go to war, we need you with your horse skills to transfer to the field artillery branch."

Mann says there was resistance at first, but the citizen soldiers gave in so they could go "over there." The National Guard organized the second and third field artillery regiments. The second was largely made up of men from Columbus, and the third was based out of the Helen Street Armory, in Mount Auburn. That regiment was split into batteries D, E, and F, all under the banner of the 37th Division.

"They left Cincinnati in early September 1917. All of the 37th Division went to Camp Sheridan, Alabama, which was just outside of Montgomery, Alabama," he says. "That training regime went from basic soldiering, all the way up through how to do their primary job."

Mann says the units spent nine or 10 months in training at Camp Sheridan before getting shipped out to France, via Canada and England.

RELATED: OKI Wanna Know about Fort Thomas' 'abandoned' homes

"Their convoy was actually attacked by German submarines. One of the ships was sunk in their convoy," he says. "But they luckily made it to England, spent a few days in England, then transferred onto a ship to get to France."

The men of Battery F landed in France, July 17, 1918. But the front lines would have to wait.

"The United States wasn't necessarily prepared to enter World War I, in a lot of ways," Mann says. "All the artillery units, when they arrived, were separated from their parent divisions and sent to Bordeaux, France, along the southwest coast of France. All these artillery units went there for additional training on the French guns, because we didn't have enough American guns made."

The regiment was issued French-made 155 millimeter cannons — heavy artillery. Mann says originally, the cannons were pulled by horse teams, which is where the cavalry experience came in handy.

Then they were ordered up to Lorraine, near Nancy, France.

RELATED: OKI Wanna Know more about the history of Eden Park's rules and regulations

"The battery fired their first shot at the enemy on October 17, 1918, which was just a few weeks before the armistice," Mann says. "They initially supported the 92nd Division, which was a segregated all-Black American division that was fighting there."

Mann says the battle lines were fixed. There was not a lot of movement one way or the other. He says the unit history indicates in the final hour of the war, they were still firing: one round a minute.

"When the armistice occurred, at 11 a.m., on November 11, it was the most eerie silence they could even imagine. Here we think the war is ending and we're going to have peace," Mann says. "And then after hearing constant firing, constant shelling for the month they were there, for all of a sudden for it to be deathly quiet was kind of an eerie sound to them."

Battery F was recognized by the French and American governments for their efforts, but the unit wasn't honored, and received no commendations. Mann says they just weren't in combat very long.

The men of Battery F returned home in April 1919.

Through the whole time, from organization to training to deployment, the unit had someone looking out for them.

"They were sort of adopted by a number of groups. The Daughters of the American Revolution chapter in Cincinnati adopted them, and sent them care packages," Mann says. "They kind of became their second mothers, if you will, and made sure all their needs were taken care of, and their comforts, and the things the Army didn't provide they helped them out with."

The regiment as a whole was immortalized in music. Cincinnati-born composer Henry Fillmore composed a march called "136th USA Field Artillery."

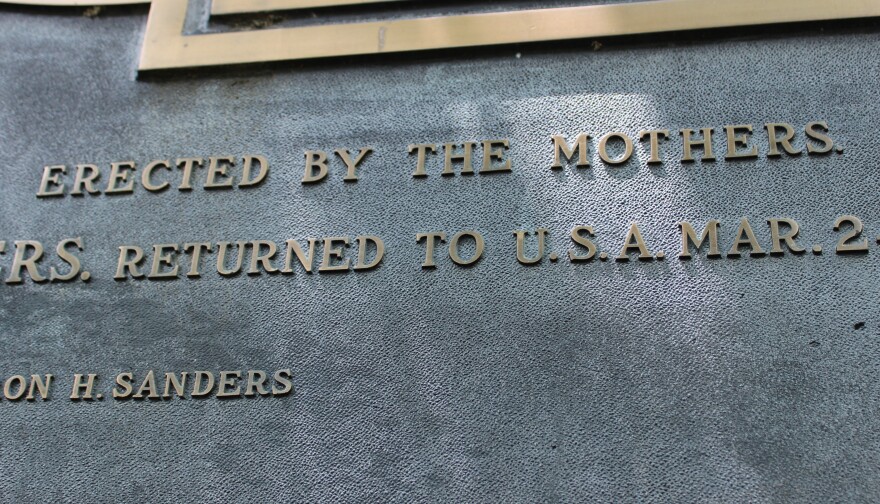

Years after the war ended, the mothers of Battery F decided to honor the men again. Mann says in October 1925, the plaque in question was dedicated.

"On the plaque it states this was erected by the mothers of the battery in memory of the unit. It lists all of the members of the battery by name; identifies those that were lost during their time," he says. "And most of the losses occurred by accident or disease. None of them were as a direct result of combat."

Mann says there's no clear reason why Battery F got a plaque and the others didn't.

"The mothers of Battery F just took the initiative and made it happen."

It's not clear if it was the actual mothers or the adopted mothers.

Mann says he's looked through the veterans' names, and none stand out as going on to do bigger, more famous things.

Today, the plaque sits on the south end of the Twin Lakes area, obscured by trees.