Dean chats with Noreen Grice, the founder of You Can Do Astronomy, an accessibility design and consulting company with a focus on making astronomy and space science accessible for everyone!

Send us your thoughts at lookingup@wvxu.org or post them on social media using #lookinguppodcast

Additional resources referenced in this episode:

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT:

Looking Up is transcribed using a combination of AI speech recognition and human editors. It may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Dean Regas: Newsflash. There's a meteor shower tonight. See shooting stars from your very own house up to 100 meteors per hour shooting across this sky. Oh my gosh. It's gonna be so good. Have you read about this? It's clickable, that's for sure. 'Cause you think, all right, shooting stars Meteor shower? This is awesome.We're gonna have the Lyrids coming up in April. It's gonna be like Laser Floyd. Everything's shooting across the sky.

Uh, see, this is where I have to bring everybody down. I have to be the buzzkill astronomer because no, you will not see 100 meteors per hour. I don't care what the internet says. I don't care what the NASA scientist that's quoted on the internet thing says it's not gonna happen.

Why am I such a downer? Why do I dislike meteor showers? Well, I guess we gotta talk about that.

From the studios of Cincinnati Public Radio. I'm your host, Dean Regas, and this is Looking Up. The show that takes you deep into the cosmos or just to the telescope in your backyard to learn more about what makes this amazing universe of ours so great. My guest today is Noreen Grice, the founder of You Can Do Astronomy, and for over 40 years has made astronomy more accessible for everyone.

[Archival TV News Audio]: It is set for this weekend. The best time to catch this dazzling display. Perseid is one of the more active meteor showers of the year, seeing about 60 shooting stars.

Dean Regas: All right, so why do meteor showers drive me so crazy? It's because it gets people's expectations really high…

[Archival TV News Audio]: Dozens streaking across the night sky, and it is intense. The intense meteor shower, one of the most active meteor showers of the year.

Dean Regas: I've gone out to so many late nights looking for shooting stars and so many late nights I've come in cold. Disappointed, tired, because you think in your mind there's gonna be like shooting stars every minute, every two minutes.

[Archival TV News Audio]: 10 to 50 per hour, even more than that!

Dean Regas: And I go out there and all these NASA people are like, yeah, you're gonna see a hundred an hour …

[Archival TV News Audio]: …Producing up to 120 meteors per hour.

Dean Regas: And I wait for like a half hour and I see one, maybe two on a good day.

[Archival TV News Audio]: And did you say somebody already started seeing them? Mm oh, A friend of mine in Santa Barbara said, yeah. Woo! Great Meteor!

Dean Regas: Well, what's going on here? Well, meteor showers are notoriously fickle beasts. We can't predict them with any good certainty, but I don't wanna like totally downplay these things 'cause shooting stars are really cool to see, and you can see them at any particular day if you're out there, if you.

Wait long enough, of course. But what we have coming up in April is a meteor shower that happens every year called the Lyrids, and they peak around April 22nd or 23rd, but you can see some stray Lyrids a couple days before, a couple days after that. Good news, this happens in April where the weather is usually a little warmer and you can stay up a little later and be comfortable.

The moon is not gonna be in the way, so Moonlight will wash out some of the fainter meteors. Bad news, Lyrids are just kind of so, so as meteor showers go, the Perseids are a lot better. Usually are the Orionids or the Geminids, that kind of thing. Am I telling you don't go out and look for the Lyrids? Absolutely not.

Do you see a couple shooting stars? Maybe you'll be like, oh, cool. But really the big show is to get out and enjoy the spring sky because you got warmer weather. You can stay outside and watch the sky. I know you're not gonna see shooting stars. Just, just put that away. You're not gonna see very many of 'em, but you will see lots of other stars out there.

And we're in this period of time where we're kind of transitioning from the bright stars and constellations of winter. Into the kind of more subtle ones of spring. So, meteor showers. Okay. Just use it as an excuse to get out there and watch some stars. Identify some new stars and constellations. You see one shooting star, you're like, woo.

Call it a good night. That's for sure. So, this is just one way to get into astronomy. We got some other ways we wanna talk about, and some ways you can even touch the stars.

Noreen Grice: My name is Noreen Grice. I have a consulting company called You Can Do Astronomy, LLC, where I make astronomy more accessible to students with disabilities and different learning styles, and especially for people who are blind or visually impaired.

Dean Regas: Well, Noreen, thanks so much for joining me today.

Noreen Grice: I'm so happy to be here.

Dean Regas: So astronomy seems like such a visual field. What did you find it was like for people who are blind or visually impaired to study astronomy back when you first started?

Noreen Grice: Well, back when I first started, I wasn't thinking about it at all. I. So I had just started working at the Boston Museum of Science in the Charles Hayden Planetarium.

And, uh, maybe I was on the job for like a month or so, and I was taking tickets for the next planetarium show, and there was a group of blind people in line, and I, I didn't know what to do, so I asked the manager, who was an older gentleman, uh, what do I do? There's some blind people in line. And he said, eh, just, just help 'em to this seat.

That's all you have to do. So I did that. And, um, then I went into the console and welcomed everyone to the planetarium and I pressed the button on the Apple two e computer to start the prerecorded show. And then my job was to sit there and, uh, move the star projector around a little bit. And then at the end of the show, um, thank people for coming to the planetarium.

[Archival Audio]: When you look up at the sky on a clear night, what do you see? There's the moon and the stars.

Noreen Grice: I was looking at that group of people during the program and I wondered what they were thinking. So, when the show was over and they were coming in my direction, I came around and I asked them how they liked the show.

Now, I expected they'd probably say, yeah, it was okay, but that's not what they said. They said That stunk. I walked away and it was like somebody like threw a brick at me. I was, this is the most wonderful place in the world. What happened? That moment in time just stuck with me and I felt like I really had to understand what went wrong.

And I, I took the bus over to the Perkins School for the Blind, and I found the library there. I walked around and I asked the librarian if they had any astronomy books, and the librarian directed me to a bookshelf with very large books, very thick, and I. I took one down and I was flipping through the pages and I saw it had braille.

And I said, do any of these books have like, uh, raised pictures that you could touch? And the librarian said, not very many Braille books have raised pictures because they're very expensive and very time consuming to make. And then it occurred to me, oh, the planetarium was not a great experience because the images were projected on the dome overhead.

They were not accessible. And that planetarium show. The narration was something like, uh, and over here is the Big Dipper and over there is Saturn. You know, and it wasn't even descriptive. And so I started to understand, well, it wasn't accessible and I don't know how to fix this, but I'm gonna try. And that moment in time, back in 1984, started me on this journey to create, uh, a world of accessible astronomy.

Dean Regas: Well, it sounds like a very daunting challenge and probably one that would take a lot of creativity. Uh, so what did you come up with and what worked and what didn't?

Noreen Grice: At first, I didn't know what to do. Remember, I went over and talked to, uh, an elderly woman who worked at the Massachusetts Association for the Blind, and she said to make, uh, raise pictures, you should glue string to cardboard.

Now, I don't know, it didn't sound too promising back in 1984, and I also was fooling around with Play-Doh and things like that. That didn't work very well. But I decided, I'm gonna try to figure this out. I went to the back to the Perkins School for the Blind, and they actually were selling these etching kits and plastic pages.

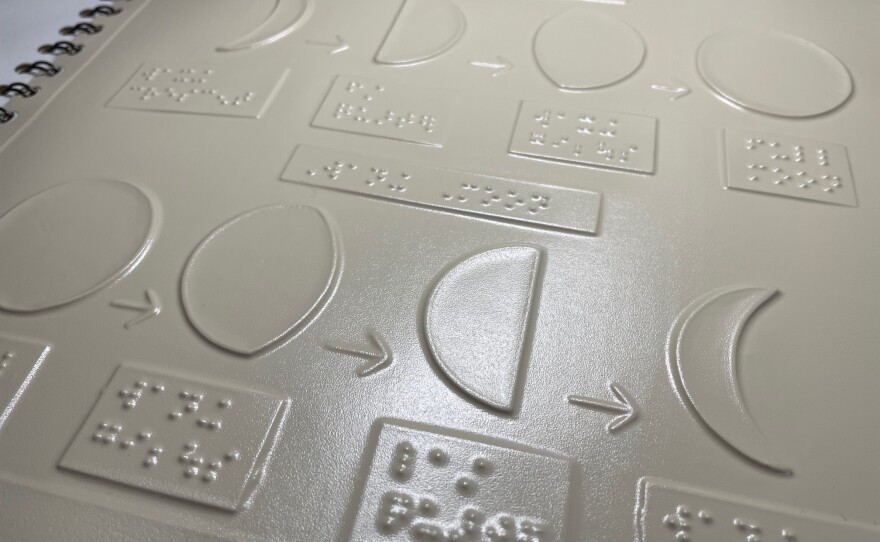

And so just with hand tools, I would be sitting at the desk at the planetarium. I. Trying to draw out the rings of Saturn and the phases of the moon because I wanted to have different pictures to go along with different planetarium shows and I needed to test them also. So I ended up going to a blind student and showing them the pictures.

Now, I was quite proud of like my Big Dipper, and I even put a caption below it. I had like a little template that had print wars and braille. The first thing the person said was, why does this picture have all letter A on it? And and I was like, what? What do you mean about that? I don't understand. And the student said in Braille, um, one.is the letter A.

If you're putting dots on a page, it looks like the letter A, unless you tell me it's not. So here I was making stars, but they look like alphabet soup on the page. And if you're gonna use a dot for a star, you need to have a key. You need to put that dot equals a star. And so I was making a bunch of mistakes, but it was great because I learned so much from the mistakes that my pictures got a lot better.

Dean Regas: I mean, it's like hilarious that they'd be feeling this and saying all the planets are a's what's going on here? So you get these initial reactions, but then what were some of the ones that were like real positive that you thought, okay, I'm on the right track here.

Noreen Grice: So, you know, the planet charm was not accessible to Museum of Science and a lot of things were behind glass cases.

And it seemed like if there was a person who was blind who accompanied somebody to the museum, some of the staff may have looked the other way 'cause they didn't know what to do and they didn't wanna do something that was wrong. So what I started to do was seeking out blind people who came to the museum.

If I heard there's a blind visitor, where's that person? And I would run down there with my pictures and I'd say, could you help me? I'm trying to make these tactile pictures. Could you look at them with me? And every time the person would say, yeah, let's sit down and take a look. And we'd feel the pictures together.

And also I started to get some small grants to. Do like recorded guided tours of the Museum of Science, and I was able to get people to volunteer to help go through the tours with me, people who were blind and they were just really happy that there was some positive efforts to making the museum more accessible, especially in the planetary where that wasn't even considered a place that was welcoming for people who were non-visual learners.

Dean Regas: Well, and then fast forward a little bit farther, and you're the, uh, the author of, of several tactile astronomy books. What are some of your favorites and which ones have you seen that have had the most impact?

Noreen Grice: When I started to make these tactile pictures for the museum, and I was going into my senior year at Boston University, I went to my professors and I said, I would like to do a directed study.

I would like to write a book for the blind. All of a sudden the room got quiet and you could hear a paper clip drop. You know, I think he, he thought, I've never heard anything like that, but I, that was the beginning of the first book Touch the Stars, and so during my senior year, I wrote the text for Touch the Stars.

I couldn't quite get how to mass produce the tactile images. But after I came back from grad school and I returned to the Museum of Science, then things really picked up. I was able to get on a, a grant, a braille embosser. I was able to start making the pictures. I had the text and the Museum of Science published the first edition of Touch the Stars with very little promotion.

I think we made, it was either 200 or 400 copies and they sold out. And as time was going on, I was creating new images and they would get added into the new version. Well, we're currently in the fifth edition and National Braille Press has taken over publication of that and where I started out with a handful of images.

We've got over a hundred pages of text, which has print and braille on it, and 19 tactile images. Touch the Stars is like an introductory astronomy book that would be good for, you know, anyone who is age eight and up, because it has all sorts of typical astronomy images. You'd be thinking about planets, constellations of eclipses, moon phases, galaxies, nebula, you know, so.

You can learn about astronomy and you can feel your way through. A person who is cited can read the book because it's got print on it. A person who is a non-visual learner can feel the braille and read it too and together, uh, enjoy the pictures. And so Touch the Stars stars has been really the foundation of all my astronomy books.

Dean Regas: Your latest book is also a digital book called Touch the Solar System. Uh, tell us more about that and what advances in technology are, are kind of helping to bring more astronomy to people.

Noreen Grice: Right, so this book, Touch the Solar System uses a device called the Talking Tactile Tablet or T3. The book will basically come alive as you're touching different places.

There are different layers of information, so you can be. Say, touching, uh, the great red spot on Jupiter, and it'll, it'll tell you about it, and then there'll be a, a little tone to tell you there's more information. So if you touch again, you can, you can go deeper and deeper. It's something that would, I think, be great in a classroom or in a library, or in a museum. I think people will really like it.

Dean Regas: Thanks Noreen, for talking out with us today.

Noreen Grice: Thank you so much for inviting me. It's been really fun.

Dean Regas: So over the past year, I've been working with the Clovernook Center for the Blind and Visually Impaired on a new astronomy book, Clovernook’s Printing House is located in Cincinnati. It's the largest in the country, producing more than 30 million pages of braille every year. And so I went to them with this idea of a book and my topic and my title of my book is called All About Orion, my favorite Constellation. I worked with the team to, you know, write up a story about Orion. I did a little bit of the mythology, but mostly I wanted to show how the stars are laid out and that people could like, touch them and feel the outlines of the constellations.

And so it was really fun working with this team to produce Orion in like this 3D format. So there was an event. That Clovernook, did called the Braille Challenge. And they had me come in to kind of field test the book with a group of kids who are visually impaired and, and blind. And we were going through the book and I was telling them the story behind Orion and the mythology.

And uh, one of the girls that was sitting next to me, I was telling the story of the, the myth is crazy about Orion. And she's like, “this story is so weird.” I was like, “Yeah, it is weird. So you, you got that right.” But then there's a page of the book where I have just stars, a star field that's raised up in tactile and they're supposed to guess which constellation it is. So it's part of the book, use your Imagination. And the constellation it's supposed to be is Ursa major, the big dog. And so when I'm showing this to the students, I'm like thinking, oh man, what are they gonna think?

First person that said something out loud was, “It's a dog!” I was like, “It's a dog. Oh my gosh, it's a dog. You're right!” Oh, so this is why you field test this stuff. And so it's really fun to work with this audience and they're so excited to be able to like learn astronomy this way. Boy, I'm really nervous, but I need to send a copy to Noreen too and see what she thinks. It was so great talking to her. She was an inspiration for the book as well.

I'm hoping All About Orion will be coming out shortly. It should be out. Any day now. So look for it in Braille and text coming out this spring.

Looking up with Dean Regas as a production of Cincinnati Public Radio. Kevin Reynolds and I created the podcast in 2017. Ella Rowen and Marshall Verbsky produce and edit our show and get totally mad at me, personally, when every meteor shower they see underperforms. It's not my fault. I didn't say it was gonna be any good.

Jenell Walton is our Vice President of content, and Ronny Salerno is our digital platforms manager. Our theme song is Possible Light by Ziv Moran. Our social media coordinator is Hannah McFarland, and our cover art is by Nicole Tiffany. I'm Dean Regas. Keep looking up.