Cincinnati council members may be voting soon to limit how and when the police department can use no-knock warrants. But whether the council has the authority to make those limitations is up for debate. And the police department has been mostly mum on the issue. But a collection of 15 years of data on no-knock warrants show they have been mostly issued in historically Black neighborhoods and Black people are most often arrested.

Proposed Changes

Last year, Louisville police killed Breonna Taylor, an unarmed Black woman, while executing a no-knock warrant at her home. This prompted local officials to take a look at Cincinnati's policies.

Council Member Chris Seelbach is from Louisville. He drafted reforms to the city's no-knock warrant procedures, along with groups like the Black United Front, Ohio Justice and Policy Center and The Black Lawyers Association of Cincinnati.

They want to limit no-knocks to life-threatening situations and require police to provide more detailed information when requesting them.

"We've had three or four conversations that have led to the legislation about really reforming the entire process and understanding that there are very specific and very rare circumstances where a no-knock warrant may make sense, where there's someone who has been kidnapped for example," Seelbach said. "But we want to severely limit them, and then really reform how warrants are served in every sense, and that's what the legislation does."

It's unclear if council can enforce such legislation or only strongly suggest changes.

But hard data on local no-knocks — how and when they're used — has been mostly missing from the conversation.

Local Data Shows Racial Disparities

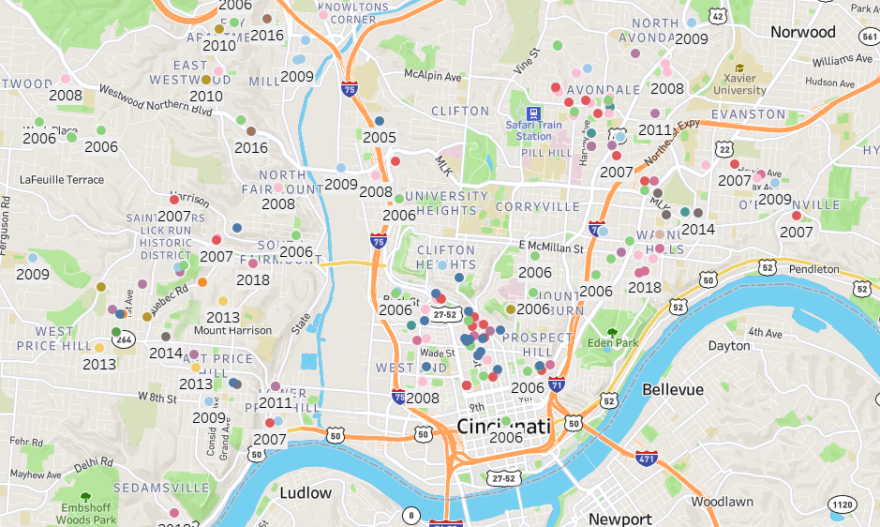

WVXU collected 15 years of data on no-knock warrants in the city, and it's clear they're mostly issued in historically Black neighborhoods and Black people are most often arrested. Police released data from all no-knocks they participated in, whether it applied for the warrant or assisted other agencies.

For an interactive look at 15 years' worth of no-knock warrants executed by Cincinnati Police, visit the Tableau website. The data is sorted and color-coded by year.

Here are the main takeaways:

- No-knocks were mostly used in historically Black neighborhoods like Avondale, Walnut Hills and parts of Over-the-Rhine.

- Police have drastically decreased no-knocks over the past 15 years from a high of 44 in 2008 to two in 2019 and none last year.

- Arrest data provided to WVXU was incomplete, but showed in the past five years, 27 of 34 people arrested were Black, and 24 of them were Black men.

- White people accounted for only 20% of those arrests and were disproportionately white women.

- The charges that spring from no-knock warrants are almost exclusively drug related.

The Cincinnati Police Department has mostly declined to comment about no-knock warrants, but they issued a brief statement saying Chief Elliot Isaac doesn't support completely taking away the department's discretion to use no-knocks, but is "open to a thoughtful review of our current process and exploring best practices in law enforcement on this important topic."

National Perspective

None of the local data about no-knocks is unique compared to national data.

Dennis Kenney, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, is a former police officer and an international researcher.

He said no-knocks are particularly risky procedures that are a product of the war on drugs dating back to the 1970s. That's why he says no-knocks are primarily used in drug cases to this day — that's what they were designed for and that's how the issue of race comes into play.

Black people are not more likely than other races to use or sell drugs, according to national research. But they're more likely to get arrested for doing so. According to data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Black people are five times more likely to be imprisoned for drug offenses than white people.

"The police will tell you that they do their enforcement because those are the neighborhoods where the crimes occur the most," Kenney says. "But if those are the neighborhoods where you police the most, then obviously the data is going to show that those are the neighborhoods where the crimes occur the most, because that's where you're identifying crimes and arresting people. So, as I said, it becomes kind of a self-reinforcing process."

And he says policing can be political. He suggested targeted and aggressive drug enforcement in primarily well-to-do white neighborhoods would likely be short-lived because those people have the most sway politically in most cities. Targeting people with less influence, he says, is the path of least resistance that results in racially biased enforcement.

Charles Stephenson is a former police officer and FBI agent in Kansas. He's exchanged gunfire with armed suspects and understands the dangers police face when doing their job. When it comes to no-knock warrants, he says they're risky for officers and the public, but sometimes necessary.

"The main issue of no-knock warrants is preservation of evidence and protection of some individual that may be held hostage or something like that," he said.

While he says police need the option to use no-knocks, it's possible for no-knock warrant reforms to work well for police departments and the public. It requires one major thing, he says: education on the part of lawmakers and police.

"If you have a mutual consideration on both sides, then perhaps you can engage in a mutual procedural redefining of no-knock warrants, warrants after dark, daytime warrants. So it's an educational procedural issue that has to be put into place," Stephenson said.

The Law and Public Safety Committee is taking up the issue of no-knock warrants this week. The meeting can be streamed at 9 a.m. Wednesday on CitiCable.