The question seems completely absurd to us in the 21st century: should we use cameras to help with astronomical research? Well, of course. Why wouldn’t we? But in the early 20th century, this was a heated debate that echoed in the domes of many established observatories around the world. So when did the camera really outshine the eye for documenting things in space? Dean Regas chats with Anika Burgess, author of Flashes of Brilliance: The Genius of Early Photography and How it Transformed Art, Science, and History, to learn more.

We want to hear from you!

Send us your thoughts on this episode at lookingup@wvxu.org or post them on social media using #lookinguppodcast

Episode Transcript:

Looking Up is transcribed using a combination of AI speech recognition and human editors. It may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print. This transcript may include additional material from the conversation, not featured in the audio.

Dean Regas: In 1911, a controversy was brewing at the Cincinnati Observatory. The issue was so powerful and so divisive that it split the local astronomy community into two distinct camps.

Differences became irreconcilable, and one astronomer broke away to form a rival observatory on the other side of town. I mean, what was the big deal? Anyway? Aren't we all just looking at the stars? Well, it pitted traditional astronomers against the new astronomers and the controversial question they faced was:

Should we use cameras?

From the studios of Cincinnati Public Radio, I'm your host, Dean Regas, and this is Looking Up: the show that takes you deep into the cosmos or just to the telescope in your backyard to learn more about what makes this amazing universe of ours so great.

My guest today is Anika Burgess. She'll talk about her new book, Flashes of Brilliance: The Genius of Early Photography and How it Transformed Art, Science and History.

Should we use cameras to help with astronomical research? Well, of course. Why wouldn't we? That question seems completely absurd to us in the 21st century. But in the early 20th century, this was a heated debate that echoed in the domes of many established observatories around the world.

In Cincinnati, it was the observatory director Jermain G. Porter, who had to decide when his younger assistant, Delly Stewart, proposed hooking up a camera. To the, then 65-year-old telescope, Porter said, thanks, but no thanks. OK. He said it probably more adamantly than that. We actually do have a lot of back and forth in the archives about this, but we'll save you.

So why wouldn't you do this, Porter? Well, because essentially photography was not as reliable or frankly as good as the eye for most things in space. To take an astro photo, back then you needed to use noxious chemicals in an unlit dome…

[From A/V Geeks 16mm Films] History Of Photography (1940s): A copper plate was made sensitive to light, exposed in a camera, and then developed with mercury fumes.

Dean Regas: And as happened frequently, you could work a whole night taking pictures and then when they're developed, you get nothing.

And if you did get usable photos, they were on bulky glass plates. And so how do you even store them? Where do you store them? Hundreds of them. Thousands of them. Porter argued that astronomers should continue to chart the stars with drawings instead. I mean, paper and pencil, a lot cheaper. Stores easily, distributes well.

Plus the eye captured more details when it came to the planets and it didn't exaggerate and overexpose the stars. So when was the turning point? When did the camera really outshine the eye for documenting things in space?

Anika Burgess: Hello, my name is Anika Burgess. I'm a writer and photo editor and author of the book Flashes of Brilliance.

Dean Regas: Well, Anika, thanks so much for joining me today.

Anika Burgess: Thank you so much for inviting me on the show.

Dean Regas: Well, take us back to the mid-1800s, like the earlier days of photography. Tell us what it was like to not only take a photo, but the process of getting your photo taken.

Anika Burgess: I mean, it was immensely arduous to take a photograph and to be honest, it sounds like it was kind of stressful to get your own photograph taken as well. Now, the reason it was arduous to take a photo at the outset of photography — and we're talking 1839 was the year that daguerreotype was introduced to the world.

But anytime, sort of in that first decade, really several decades after, there were many chemicals that photographers were dealing with. They were trying to judge exposures without having light meters. And of course, photography requires light. And this was a time in which there was no electricity that was being tapped into people's homes and specifically photo studios.

And then in terms of going to have your own portrait taken, I mean, there were many challenges there. And there's several humorous accounts of people going to have their daguerreotype taken. And even with the later processes as well and being really quite horrified as to how they appeared in this cold, metallic black and white image.

There's even cases of people suing photographers for their bad portraits. They were so outraged with how they looked. So it was a time of great experimentation. And also I think some wounded egos.

Dean Regas: And how popular was it in the early days? Were people like, were they skeptical of it, scared of it, and was it even affordable?

Anika Burgess: I mean, it was utterly revelatory. So when the daguerreotype was first introduced, there's some letters of Americans and English men in Paris seeing a daguerreotype for the first time. And I remember one account said that it baffled belief, you know, that this man could not understand what he was even seeing, that there was this actual accurate representation from life on a metal plate. It was not especially affordable at first, and it wasn't even possible to get the portrait taken at first because the exposure times were too long. But I think because it was so revelatory that within a couple of years there were improvements to both chemicals and to optics, and it meant that portraits were then possible.

Still long exposure times, but we're not talking 20 minutes, we're talking, you know, depending on the time of year, depending on the light, it was sort of range between my understanding of sort of like 30 seconds to a minute and a half.

Dean Regas: Well, let's shift to astronomy. And so I know in studying the first telescopes, those were mainly used to look at things on Earth. And until Galileo famously pointed the telescope skyward, how long did it take photographers to aim at the heavens and who were like the pioneers of astrophotography?

Anika Burgess: I mean, it was immediate. I mentioned earlier the daguerreotype was announced in 1839. It was actually announced, not by Daguerre himself, but by a French scientist called Francois Arago.

And in his announcement, he said, this is gonna be a game changer for all of these aspects of life and science, including specifically mapping the moon. We will have this instantaneous picture of the surface of the moon, a job that would otherwise take us, you know, weeks, if not months by hand, and Daguerre himself.

Reportedly had a daguerreotype of the moon, but it was lost. The one that exists, the oldest known daguerreotype of the moon that exists was actually taken in New York by a man called John William Draper. It was a 20-minute exposure. It is a fascinating image. It's online if anybody wants to take a look at it.

One of the things I love about this image is its afterlife. It was actually kind of lost for a period of time, and then it was discovered in the attic of a library in 1961, and its history was realized at that point. So, so early, early on, there was this sense that there's an opportunity here to capture what was regarded as an accurate visual representation of the moon.

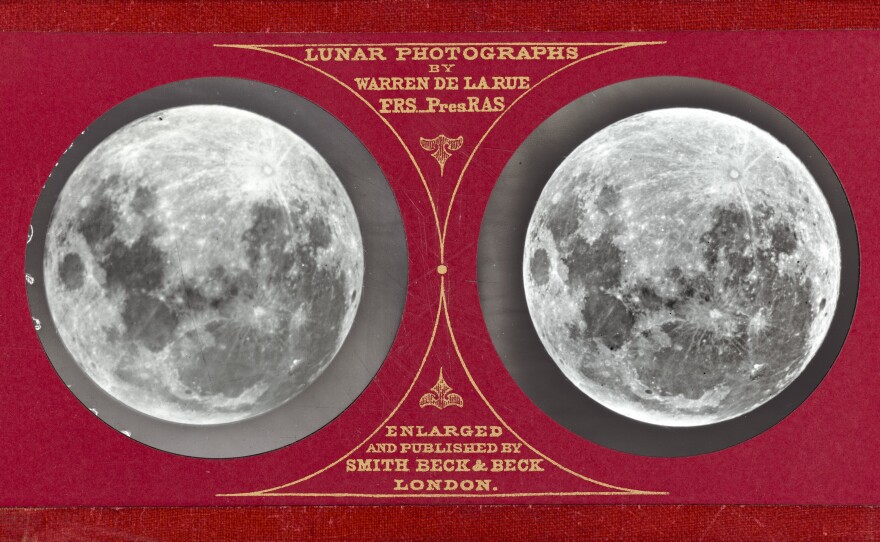

Of course, there's a — when it comes to accurate representation — this time because experimenters that I talk about in Flashes of Brilliance, one being Warren de la Rue, who was a businessman and an amateur astronomer, and one called James Nasmyth, who was also a businessman and an amateur astronomer.

Dean Regas: Well, and I think this is the part that probably fascinated me a lot, is how do you actually get an image back in the day, you know, what's the process? Or there were various ways of photographing things that seemed kind of dangerous or at least involve noxious chemicals.

Anika Burgess: Absolutely. I mean, across the board, noxious chemicals were involved. There were even photographers who opted to use cyanide in their darkrooms, which was not necessary and was an extremely bad idea, and nobody should do it, just in case it's not already very obvious.

And it's true that the other issue that specifically Warren de la Rue was dealing with, and he began his photography of the moon in the 1850s, was he was dealing with the wet collodion process, which very briefly was the process that came after the daguerreotype. It involved a lot of chemicals.

Collodion was combustible, but the real issue with it was that you had to prepare and expose and develop the plate while it was still wet. So we're talking like a short, 15-minute-ish, 20-minute-ish timeframe. So he was not only dealing with the telescope that he was trying to track the moon and it was 10-foot long and he had to uncap it and recap it.

He was also rushing around from the darkroom to the telescope to try to expose the plate and develop it and actually get a clear picture.

Dean Regas: Well, so you're in the observatory, you're in the dome, and best-case scenario, you do all this work in the dark with noxious chemicals and you actually get usable photographs of the moon, stars, things like that. How do you share them with the public? How do you distribute images?

Anika Burgess: I mean, this is the great other aspect of lunar photography in the mid-19th century. And this is what John William Draper came across with his daguerreotype is that, you know, a daguerreotype was a one-of-a-kind image. It couldn't be reproduced and it's really easy to forget as well at this point that.

Newspapers and magazines could not reproduce photographs either. They could only do wood engravings, basically, which was an artist's interpretation of the picture. So for someone like Draper, you know, his daguerreotype couldn't be very widely seen. And this is where I think I find Warren de la Rue and James Nasmyth so fascinating because they both took slightly different approaches to sharing with the public.

Their images of the moon in particular was fascinating because he really used another key technology of the day, not just photography, but something called a stereoscope, which your listeners may be familiar with, this device that you look through. And there's two images that are roughly eye width apart and they create this three-dimensional image, and he really seized upon that at the height of its popularity in the 1850s and created a stereoscope, three-dimensional images of the moon, people to bring home, look at in their parlor and wonder at.

Dean Regas: Well, and you know, I've heard the stories from the old-fashioned astronomers who are not so taken in by this astrophotography thingy. They greatly preferred like drawing what they saw through the telescope with their eyes. And I think it's kind of quaint thinking that, you know, you have this artist astronomer drawing things over photographing. Did they have a case? Was drawing better than taking a picture?

Anika Burgess: I mean, this debate went on for some time, you know, and there were certainly those that felt drawing was really the best way to do it. There was not a lot to be added, simply because, you know, the moon was so far away and the lenses could only do so much.

And then there were those like de la Rue who really wanted to show the moon in its accurate detail and its form, and its heft and its weight. And so he was really pushing toward the direction of astrophotography. But for a long time it was really this kind of state of flux, not just lunar photography.

Which is what really I'm focusing on when I talk about de la Rue and James Nasmyth and those early images by Daguerre and Draper, but really other aspects of astrophotography, whether it was the Transit of Venus, which was attempted to be photographed in 1874 or any other sort of celestial bodies.

Dean Regas: Well, it seems there was this kind of a little bit of suspicion, especially among the old-fashioned astronomers and maybe even the question is, is a photograph actually real?

Like, are they actually photographing things? I mean, you have longer exposures. You got tricks that make people think like photos, almost like we think of AI now. Was it reality, hyper-reality?

Anika Burgess: This is a theme that comes up in my book a couple of times because, you know, as I've talked about already, photography was born from science. It was seen as being this very accurate representation because it was coming from optics and chemistry. It was not this artistic thing. And there were those that pushed against that and said, no, photography can be artistic. We can create images from our imaginations with image manipulation. And then there were those that believed it only had this role in science.

So this tension between the two was not only in astrophotography or lunar photography, it was really happening across the board. And it is fascinating, and as you rightly say, to a degree, it has evolved and it's still with us today.

Dean Regas: Well, Anika, this has been so much fun. Thanks for chatting about your book and we're really excited about it and this has been a lot of fun.

Anika Burgess: Thank you so much. I've enjoyed it a lot, Dean.

Dean Regas: Well, the newest astronomy craze is around telescopes that are small, portable, and take photos. You can take them outside, set them down, get a GPS signal, and then guide them with your phone to targets all around the universe. They'll locate, track and photograph nearly any object. And you can do this from cities despite light pollution, and then you can share the pics to other phones.

Pshh, I say cheating. Back in my day, we had to get the data from professional observatories if they published them at all, or work really hard on our own and try to figure out how to process film. Now you can get a scope to do all of this for under $350. Ridiculous. Well, some of these new astrophotography scopes don't even come with an eyepiece, meaning it's just a glorified digital camera.

I was working at a star party this fall where I had my optical telescope set up next to a newfangled digital one. People could actually look through my telescope. They could put their eye up to it, but people were still amazed by the technology over there at the other telescope. The astronomer over there said, look at the picture of the Andromeda Galaxy it took. Ooh. Ah, that's amazing, everybody said. I was over by that old telescope and I was not impressed. I wanted to go over with my phone and say, with similar gravitas, Hey, look at the picture of the Andromeda Galaxy I just got from Google. You know, both seemed equally difficult to do and similarly real. Well.

Now last, I probably need to get over it because these telescopes are coming around and maybe I need to get with the new fads. Nah.

Looking Up with Dean Regas is a production of Cincinnati Public Radio. Kevin Reynolds and I created the podcast in 2017. Ella Rowen and Carlos Lopez Cornu produce and edit our show and use only the latest technology, which seems like magic to me. Jenell Walton is our vice president of content, and Ronny Salerno is our digital platforms manager.

Our theme song is Possible Light by Ziv Moran. Our social media coordinator is Hannah Pflum, and our cover art is by Nicole Tiffany. I'm Dean Regas. Keep looking up!