Writer Lucy Sante has been asking herself "Who am I?" for the better part of her life.

Sante, who was assigned male at birth, says changing genders was a strange and electric idea that lived in the recesses of her mind for years. Then, in 2021, she was playing around with a gender-swapping feature on a face-altering app and she had a breakthrough.

"It was uncanny, ... irrefutable," she says of seeing herself as a woman on the app. "I had no choice — I came out to my shrink 10 days later."

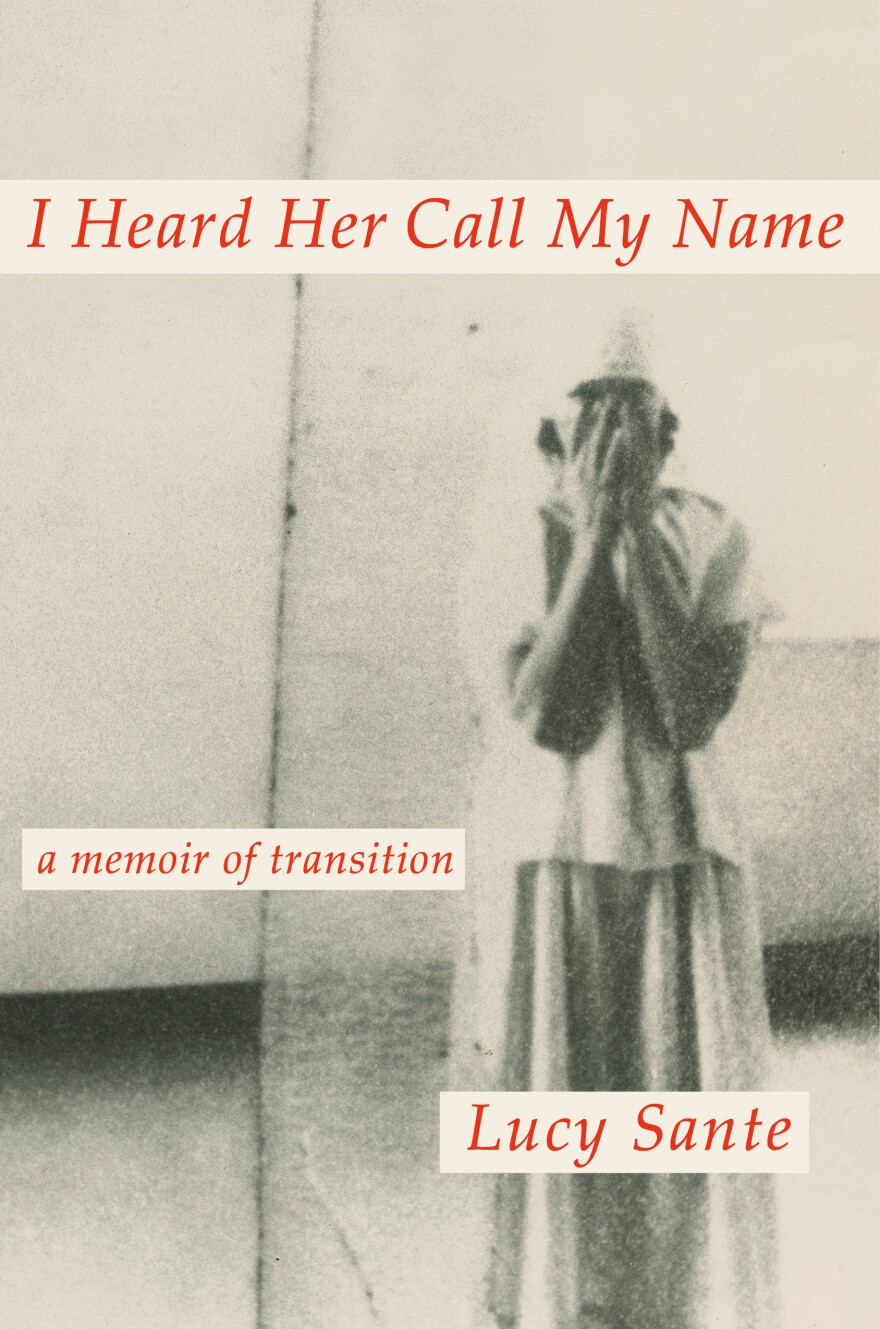

Sante is known for her incisive criticism and cultural commentary for The New York Review of Books. In her new memoir, I Heard Her Call My Name, she writes about coming out as a transgender woman at the age of 67.

Sante says her transition came after decades of avoidance. In the 1980s and 1990s, she worked a block away from Tompkins Square Park, a hub of the New York City trans scene and host of Wigstock, an annual drag festival.

"I could hear the [Wigstock] festivities from my office, but I'd wait until everybody had gone home before I'd slink back up the side of the park to my apartment," she says.

Sante says she yearned for somebody to come along and pull her into the Tompkins Square Park scene — but she was also "terrified" at the possibility: "This was the kind of internal war that raged in me for decades."

When she did finally come out to her friends in 2021, Sante says some were taken aback, but "generally everybody was cool." Since her transition, Sante says she can feel the tensions in some of her friendships relax.

"I'm just better at talking to people now because I'm not hiding anything," she says. "I was inhibited from real intimacy with really anybody because at any moment I could blab the wrong thing. ... It just haunted me for all these decades. So I think I'm probably a better friend with all of my friends than I was here before this."

Interview highlights

On coming out to her wife and son

I knew that my romantic relationship would not survive this. We're still best friends, but I knew that the romance part was not going to survive. ...

[My son] was totally chill. Because he's Gen Z. My son is now 24. He is, as I'm fond of saying, straight as a highway in Texas. But he's known trans kids since he was 11. ... He did LARPing — live action role playing — which really brings out the trans kids. He didn't bat an eyelash.

On worrying about changing her name

Why would I think that this would present any kind of difference in my career? ... My last name is rare and I'm only changing one letter. But the fact is that that was a kind of cover for a deeper existential reckoning with myself. ... I guess there's always been a kind of unstable relation between my inner self and what I show the world. Rather than changing my gender, per se, was changing my name that set off this weird kind of existential freefall. Like, who am I? This bizarre uncertainty that manifested as this completely ridiculous fear.

On her 1998 memoir, The Factory of Facts, in which she avoided personal reflection

I was dodging self depiction. And it's clear to me now, and it's a weakness of the book. And the fact is that I've recently realized, from writing this book, in which most of my close friends make appearances, I'd never really been able to write about people before because somehow there was a chain of constraints, beginning with the fact that I was trying to hide the secret. ... So everything I wrote was nicely written, deeply researched ... but it lacked that personal quality because I was unready to face who I was. I told myself regularly how I was being a hypocrite. ... The interesting thing is that since I've transitioned, I become brutally honest. I can't lie anymore. And I tend to speak my mind sometimes a little too loudly, and indecorously. I was painfully aware of that that gap, the between intention and actual result, and it's really set me free as a writer as well now.

On loneliness and happiness existing simultaneously

There's a whole series of paradoxes here, and one of them is the fact that while I'm extremely lonely much of the time, I'm also much happier than I've ever been.

Transitioning has shown me whole new landscapes of loneliness that I didn't even know existed. I'm a love junkie. Always have been, and I suffer from withdrawal when I don't have it. But also, I don't know very many trans women. ... Sometimes when the mood is wrong, I can feel like I'm living on my own separate planet or far away from anyone else. There's a whole series of paradoxes here, and one of them is the fact that while I'm extremely lonely much of the time, I'm also much happier than I've ever been.

Sam Briger and Seth Kelley produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2024 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.