Once Dave Parker ended his 19-year career in major league baseball in 1991, he knew full well that he belonged in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

But it took over 30 years for the Hall of Fame to realize it.

Sunday, in Cooperstown, N.Y., Parker will be inducted into the Hall of Fame at long last. But the man known to baseball fans as “the Cobra” won’t be there to revel in the moment. On June 28, Parker died after a 13-year battle with Parkinson’s disease, just weeks before the induction.

Parker, whose family followed the Black migration of the 1950s from Mississippi to Cincinnati, grew up in the Cincinnati’s West End, went to Courter Tech High School (now Cincinnati State College) and worked as a vendor at Crosley Field as a teenager, watching the Reds and the baseball heroes of his youth, Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson.

By 1973, he found himself at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium, wearing the uniform of the Pittsburgh Pirates and taking on one of the most daunting tasks any ballplayer could imagine — taking over right field from one of the most revered and talented players ever to play the game, the late Roberto Clemente.

In his 11 years as a Pirate, he was superb.

And he was a genuine character. A colorful, outspoken, funny character who was not shy about tooting his own horn.

A baseball writer once asked Parker why he wore a Star of David necklace, even though he wasn’t Jewish.

“Because my name is David,” the Cobra said, “And I’m a star.”

He had every right to brag about what he could do on a baseball field.

Look at the record: How could you not be considered a Hall of Famer if you amassed these numbers in your career?

- 1978 National League MVP

- 7-time National League All Star

- 3 Gold Gloves

- 2 batting titles

- 3 Silver Slugger awards

- 2 World Series championships

- hip ring with the 1979 Pirates

How could this not be a Hall of Fame career?

And yet, he was on the Baseball Writers Association of America’s ballot 15 years, through 2011, and never got more than 24% of the vote. A player needs 75% for induction into the Hall of Fame.

It was likely because Parker was one of 11 players suspended by then-commissioner Peter Ueberroth for involvement in drugs. Parker was one of seven suspended for a year, but they were allowed to continue playing if they agreed to donate 10% of their salaries to drug abuse programs, submitted to random drug testing, and contributed 100 hours of drug-related community service.

Parker, who was with the Reds at that time, did all of those things; and there was never another stain on his record.

Parker wrote an acceptance speech for his Hall of Fame induction that he held onto for all 15 years of his Hall of Fame ballot eligibility but never got to deliver.

His son David will read that speech Sunday at Cooperstown.

Dave’s wife, Kellye, will be there as well.

And, of course, Parker’s former teammate and close friend, shortstop Barry Larkin, now a Reds TV broadcaster. Larkin has sat on the stage with his fellow Hall of Famers every summer since his own induction at Cooperstown in 2012, but this year it will be even more special because the Cobra is going into the Hall as part of the class of 2025.

On June 28, the day of Parker’s passing, 31,380 were in Great American Ball Park for the on-field celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Big Red Machine and its back-to-back 1975 and 1976 World Series champion Cincinnati Reds.

The field was full of Reds legends — Johnny Bench, Tony Perez, Cesar Geronimo, Ken Griffey and about two dozen of their teammates from the Big Red Machine.

And as that celebration came to a close, the left field scoreboard flashed a photo of Dave Parker, framed in black, as Reds public address announcer Joe Zerhusen announced that Parker had passed away at the age of 74, and asked the crowd to stand for a moment of silence.

It was a stunning moment — especially with all the Big Red Machine legends still on the field.

Most of us in the ball park knew intuitively that while Parkinson’s disease is not fatal, it leads to breakdown of motor functions that always leads to death. I certainly do; both of my grandmothers died of complications from Parkinson’s.

But, still, it was stunning as the idea of baseball without Dave Parker sunk in.

I had seen Dave several times at Reds Hall of Fame functions during the time he was first diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2012 until his death this summer. The symptoms grew worse with each passing month.

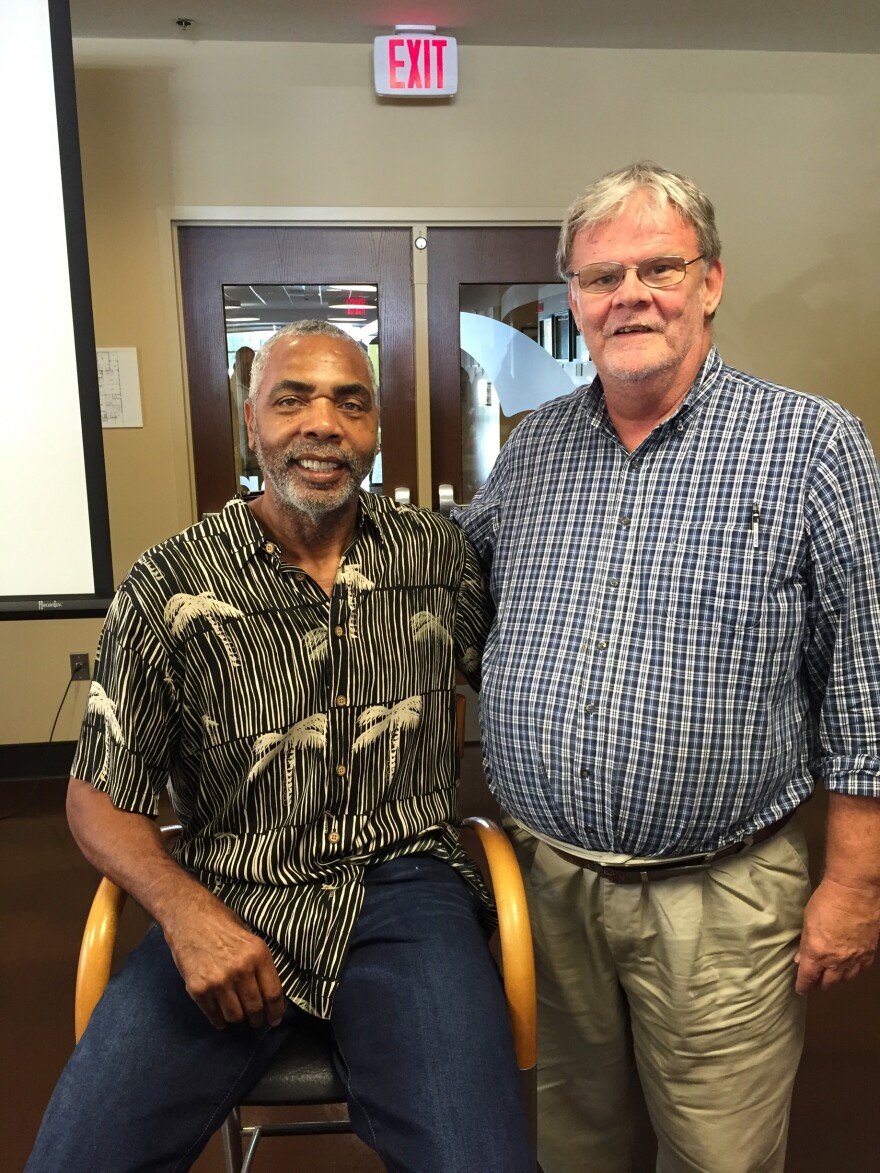

Rick Walls, the executive director of the Reds Hall of Fame and Museum, saw the same progression as this once powerful, healthy athlete went steadily downhill. Walls presided over the 2016 ceremony in which Parker became a member of the team’s Hall of Fame.

After a memorial service for Parker on July 10 at Corinthian Baptist Church in Bond Hill, Walls talked to WCPO about Parker’s determination to carry on, despite physical challenges he faced.

Even as he battled the effects of his disease, Parker continued as long as he could to hold baseball camps to teach the game to inner city kids, Walls said.

“I can be successful if I try hard, if I persevere — that's what Dave did, he fought through challenges," Walls said. “He will continue to impact people even though he is gone.”

Read more: