The police shooting of Black men — culminating with the death of 19-year-old Timothy Thomas — sparked days of civil unrest in Cincinnati in 2001. Protests, in some cases, turned destructive. More than 800 people were arrested for violating a curfew imposed by the mayor. An economic boycott put a financial dent in Downtown events.

This all happened two decades ago after Thomas was shot and killed while running from police. He was wanted for several nonviolent misdemeanors, most of which were traffic citations, reports say.

But the narrative of what happened to Thomas is familiar: Black men, teens and women, many of them unarmed, being killed by police at higher rates than any other race.

Black people are killed at a rate of 35 per million, while white people are killed at a rate of 14 per million, The Washington Post reports.

But what does criminal justice look like in Cincinnati now? How has Over-the-Rhine, where Thomas was killed, changed since the shooting?

Use of Force, Shootings

Arrests and use of force incidents by CPD have fallen precipitously since 2000; however, that mirrors a national trend in most major cities and likely can't be entirely explained by police reforms here. Meanwhile, Black people in Cincinnati are still more likely to be the subject of use of force, shootings, no-knock warrants, arrests and mairjuana violations.

In 2000, there were 1,266 use of force incidents locally. Roughly 68% of those (857) were against Black people, though the data for some incidents does not specify race.

Last year, there were 345 use of force incidents locally. Seventy-five percent were against Black people in a city where the race makes up roughly 43% of the population.

Five year samples of shooting data from CPD shows 15 officer-involved shootings between 1996 and 2001, eleven involving Black men. Between 2016 and 2020, there were 13 police-involved shootings of people. Of those, nine involved Black people.

In 2020, one person was shot in the back by an officer during a scuffle while police arrested him. But police Chief Eliot Isaac says the incident was an unintentional shooting and "not an appropriate use of force."

Police Chief Eliot Isaac will be discussing some of this data on Cincinnati Edition Tuesday at noon. Listen to the program here.

No-Knock Warrants

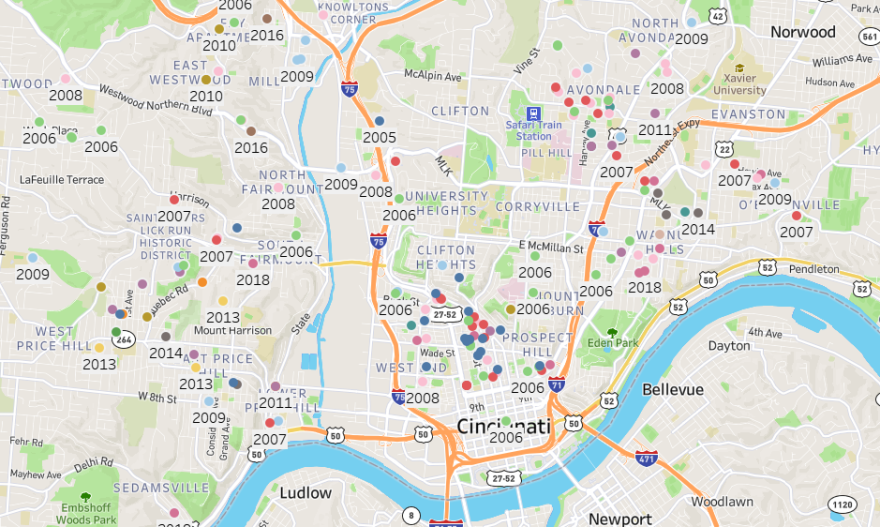

No-knock warrants in Cincinnati, like the kind thrust into the national spotlight due to the killing of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ky., have drastically decreased over the past 15 years, with a high of 44 in 2008 to two in 2019 and none last year.

But when police use them, they're more likely to be used in historically Black neighborhoods like Avondale, Walnut Hills and parts of Over-the-Rhine.

Arrest data from no-knocks provided to WVXU earlier this year was incomplete, but showed in the past five years, 27 of 34 people arrested were Black, and 24 of them were Black men.

White people accounted for only 20% of those arrests and were disproportionately white women.

The Cincinnati Police Department has mostly declined to comment about no-knock warrants, but they issued a brief statement saying Chief Elliot Isaac doesn't support completely taking away the department's discretion to use no-knocks, but is "open to a thoughtful review of our current process and exploring best practices in law enforcement on this important topic."

The Law and Public Safety Committee was scheduled to look at no-knock reforms, proposed by Council Member Chris Seelbach, in February. But the issue has been sidelined while officials say they've been working on the issue behind the scenes.

Seelbach and Committee Chair Christopher Smitherman have not returned requests for interviews about the status of the issue.

Update 01/07/21: The Cincinnati Police Depart released a statement saying, "Our review of the recommendations and areas for improvement is ongoing. We will provide a report to the Law and Public Safety Committee at the conclusion of our work."

To see an interactive map of 15 years worth of no-knock warrants executed by the CIncinnati POlice Department, click here.

Other Crimes

Black people aren't just more likely to face serious consequences from police. They're also more likely than white people to face consequences for more minor crimes.

A 2019 investigation by The Cincinnati Enquirer and Eye on Ohio showed police conducted 120% more traffic stops in neighborhoods that were 75% or more Black between 2009 and 2017. And arrests resulting from those stops involved Black residents 75% of the time.

Overall, Black residents made up 57% of all stops of pedestrians or drivers by officers in Cincinnati.

Chief Isaac told WCPO last year, "The data is where we find ourselves being taken to the same places … It turns out that those locations tend to be communities that are of color. They tend to be in communities that are more poverty-stricken, communities that have challenges with education and a myriad of things."

Similar disparity arises when comparing data about marijuana citations, arrests and violations.

City Council voted to decriminalize possession of less than 100 grams of marijuana in 2019. That should mean no fines, jail time or employment disclosure would be required.

But council doesn't have the authorization to overhaul state law, which requires a citation and $150 fine for having 100 grams or less of marijuana.

In 2020, 426 Black people were warned, cited or arrested for being in possession of 100 grams or less of marijuana. Fifty-one white people received the same consequences.

In fact, data released by the Cincinnati Police Department shows there were some months of the year when no white people were cited for low level marijuana offenses. That's not true of any months for Black people.

Chief Isaac briefly addressed the discrepancy in numbers during a virtual town hall in late January. He said he can't know the reasoning behind the data without knowing the details of the cases.

He suggested, as he did with racial disparities in traffic citations, poverty might be a factor.

Changes In Over-the-Rhine

Criminal Justice is not the only issue that has changed since 2001. Over-the-Rhine, where Timothy Thomas was killed, has also changed.

With the notorious crime rates and much of the neighborhood falling into disrepair, the city of Cincinnati and the business community decided to spend $30 million to buy up 200 buildings in the early 2000s. They did it through the City Center Development Corporation (3CDC).

The move has funneled millions of dollars into efforts to expand and renovate Race and Vine streets, Washington Park, and build condos and townhomes. Some affordable housing was also built. Hip restaurants, bars and shops cropped up, too.

But the investment into the neighborhood changed the racial makeup of Over-the-Rhine.

According to the U.S. Census, just under 6,000 Black people lived in Over-The Rhine in 2000. Ten years later, that number dropped to 4,361.

Reporters Nick Swartsell, Cory Sharber, and Ann Thompson contributed to this reporting.

This article is part of WVXU's special series looking back at the civil unrest of 2001 on the 20th anniversary of the event. Read more here.

We acknowledge in 2001 it was common to call what happened in Cincinnati April 9-14 a "riot." So why aren't we calling it that now? Through re-examining the events of 2001 and similar occurrences over the past 20 years, we acknowledge "riot" is a racially fraught word that doesn’t depict the full complexity of these multifaceted situations. We believe words like "civil unrest" or "uprising” better reflect what occurred in Over-the-Rhine in terms of many people mobilizing to seek structural societal changes following the killing of Black men by Cincinnati Police.

To learn more about how Cincinnati Public Radio is addressing racism and inequality in our coverage and in our community, please see our Statement on Diversity and Inclusion, and share your feedback by emailing newsroom@wvxu.org.