Cincinnati voters will decide this election whether the city can execute a plan to sell the only municipally owned railroad in the U.S. to a private corporation.

The proposed sale of the Cincinnati Southern Railway to Norfolk Southern has sparked opposing paid campaigns and a lot of questions. WVXU has compiled answers to some of the most common ones.

Editor’s note: This post will be continuously updated between now and the Nov. 7 election. The topic is as complex as it is important; WVXU reporters will continue to investigate and expand this resource over time.

Produced with assistance from the Public Media Journalists Association Editor Corps funded by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, a private corporation funded by the American people.

Questions about the proposed sale:

Click to jump to that section of the article.

1. Why did Cincinnati build a railway?

2. What is the Cincinnati Southern Railway today?

3. Who manages the Cincinnati Southern Railway?

4. Who operates the Cincinnati Southern Railway?

5. Why do some city leaders want to sell the railway?

6. What will I see on the ballot?

7. Has anyone tried to buy the CSR before?

8. Could the CSR be used for passenger rail, at least in theory?

10. How much money does Cincinnati get per year under the current lease? Who decides how it’s spent?

12. Who negotiated the sale price and how did they reach $1.6 billion?

13. How much money would the city get per year after the sale? How is that amount estimated?

14. Who would decide how the sale revenue is invested?

15. Who would decide how the investment income is spent?

16. How much is the Cincinnati Southern Railway worth?

17. What kind of government oversight is required for the sale to go through?

18. Would the city lower taxes if the sale is approved? Or promise not to raise taxes?

19. Could the city sell the CSR to another railroad company? Or to anyone for another purpose?

20. What happens if the sale proposal fails?

21. Who is funding the campaign in favor of approving the sale?

22. Who is funding the campaign opposed to the sale?

23. What are the arguments against selling the Cincinnati Southern Railway?

24. Why do city residents get to decide whether the railway is sold?

25. If the sale goes through, how would the city's overall budget be affected?

27. Did enslaved people build the Cincinnati Southern Railway?

29. What guidelines are in place to prevent abuse of the trust through high overhead costs?

31. What happens to the current CSR Board of Trustees if the sale goes through?

33. Who would pay the closing costs?

34. How much land does the city own along the entire Cincinnati Southern Railway?

1. Why did Cincinnati build a railway?

By 1860, Cincinnati was the fourth largest city in the country and its location on the Ohio River gave it strategic importance for commercial business as a hub for both imports and exports. The advent of rail transportation diminished the city’s importance and local leaders feared being cut out of the economy.

City officials wanted a rail corridor to connect Cincinnati with the South, but the Ohio Constitution prohibited counties, cities and towns from financially partnering with private businesses. In other words, Cincinnati couldn’t loan money to an existing rail company. In 1868, E. A. Ferguson put forth a “remarkable proposition” that the city of Cincinnati should build and own a southern railway. The city spent $578.90 lobbying for the measure in Columbus.

Columbus wasn’t the only hurdle. The proposed line would begin in Cincinnati, but would primarily run through Kentucky and Tennessee. It took several years for legislation to be passed in those states before construction could begin; the first work started in late 1873 on a tunnel through King’s Mountain in Tennessee. The final rail was spiked into place on December 10, 1879.

LEARN MORE: Why does Cincinnati own a railroad?

It cost the city $18 million to build the original Cincinnati Southern Railway.

“It had always been hoped that Cincinnati would be able to break even on the operation, and perhaps even realize a profit,” wrote Tod Jordan Butler in a 1971 thesis. “But the main purpose of the [rail] road was to strengthen the city’s commercial position in relation to the South, to provide her merchants and manufacturers with a means whereby they might recapture the lost dominance in southern markets.”

Learn more about the history of the CSR online here: cincinnatisouthernrailway.org/about/historical-timeline.

2. What is the Cincinnati Southern Railway today?

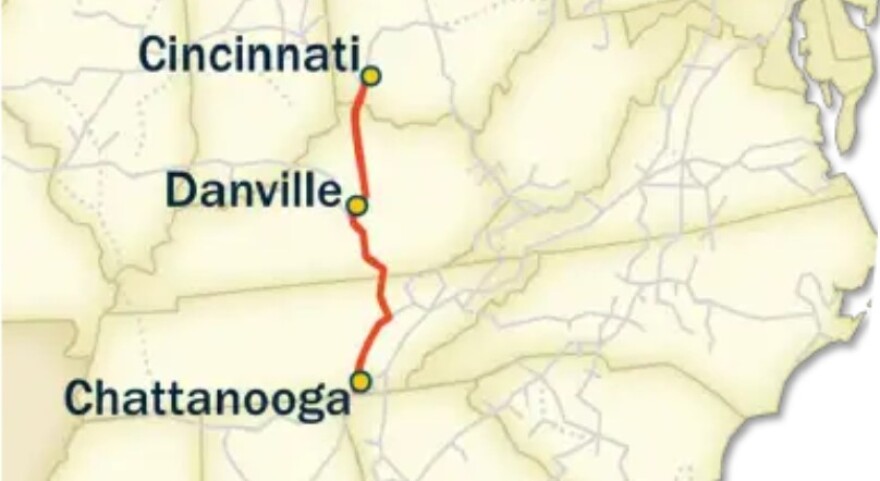

The CSR consists of railroad tracks that span about 337 miles between Cincinnati and Chattanooga, Tenn., plus signals, tunnels, and other fixed infrastructure. Cincinnati has never owned rail cars nor operated rail traffic for either passengers or freight. The railway has always been leased by a separate entity that owns and operates railroad cars, originally for both passenger travel and freight, although in recent years, exclusively for freight.

3. Who manages the Cincinnati Southern Railway?

Per the state law that allowed Cincinnati to build and own a railroad, the Cincinnati Southern Railway is managed by a five-member Board of Trustees. Board members are appointed by the mayor of Cincinnati and approved by majority vote of city council. Terms are five years and there are no term limits. There is no compensation for serving on the board.

According to the board’s bylaws, no more than three members may be of the same political party at any time. The Board of Trustees is an official public body, meaning it is subject to the Ohio Open Meetings Act. A city attorney serves as clerk to the board.

Current members (see bios on the CSR website):

President Paul Muething (Republican, first appointed by former Mayor John Cranley in 2018)

Vice President Charles Luken (Democrat, first appointed by former Mayor Cranley in 2018)

Treasurer Paul Sylvester (Democrat, first appointed by former Mayor Charles Luken in 1984)

Mark Mallory (Democrat, first appointed by former Mayor John Cranley in 2018)

Amy Murray (Republican, first appointed by former Mayor John Cranley in 2019)

4. Who operates the Cincinnati Southern Railway?

The Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific Railway Company (CNOTP), a subsidiary of Norfolk Southern, holds the current lease to operate on the Cincinnati Southern Railway. They have held a lease to operate on the CSR since 1881.

The current lease is set to expire in 2026, but Norfolk Southern had the option to extend the lease another 25 years and has already decided to do so. That means they will retain control of operation until 2051, even if the city sells to another company.

Norfolk Southern also has full responsibility, including financially, for maintaining the railway.

5. Why do some city leaders want to sell the railway?

City officials say they want to maximize the financial benefit of the Cincinnati Southern Railway and say the best deal for taxpayers is to sell instead of continuing to lease.

CSR Board of Trustees President Paul Muething says the railway started out as a strategic asset — a way to ensure Cincinnati could keep participating in the broader economy. Eventually, the railway became a way for the city to make money by leasing it out.

“It's no longer a strategic asset, we look at it as a financial asset,” Muething said at a meeting in July. “And our job from Day One has been to maximize the value of that financial asset … take that asset and make the most of it for the citizens of Cincinnati.”

Muething says the way to do that is to sell the Cincinnati Southern Railway to Norfolk Southern for $1.6 billion and invest the money, growing the balance over time and using the earned interest to pay for maintaining city infrastructure.

The financial argument has two elements:

- Estimates show the city will get more money per year by selling compared to leasing

- The “guaranteed” yearly income from a lease could eventually disappear because the future of the rail industry is uncertain

“Instead of having all of our financial future with one company, we would be able to diversify it,” said CSR Board Member Amy Murray. "I think the sooner we do that, the better and the safer it will be for the city."

To learn more, WVXU spoke to FreightWaves Senior Staff Reporter Joanna Marsh, who has spent the past decade reporting on the freight rail industry.

Marsh says autonomous trucking is certainly coming, but, “I don't think it could actually fully ever replace freight railroads,” she said.

Marsh says trucks, autonomous or not, couldn’t take on all the freight currently moved by rail without investing significantly in expanding and/or adding highways. Rail infrastructure is already there, however. Even if it does cost a lot of money to maintain, it’s still cheaper than starting from scratch, she says.

City officials are also quick to point out the city’s massive and growing deferred maintenance problem; income from investing the sale revenue would be limited to maintaining or improving current infrastructure.

The sale is supported by: Mayor Aftab Pureval; City Manager Sheryl Long; a majority of City Council Members; all five members of the Cincinnati Southern Railway Board of Trustees; former mayors David Mann and Roxanne Qualls.

“Five previous mayors of the city of Cincinnati, spanning more than 40 years of service, have come together to stand with Mayor Pureval in urging voters to support the biggest deal the city of Cincinnati has ever faced,” Mallory said at a recent press conference. “We are urging the voters of Cincinnati to approve the sale of the Cincinnati Southern Railway.”

6. What will I see on the ballot?

"Shall the Cincinnati Southern Railway Board of Trustees be authorized to sell the Cincinnati Southern Railway to an entity, the ultimate parent company of which is Norfolk Southern Corporation, for a purchase price of $1,600,000,000, to be paid in a single installment during the year 2024, with the moneys received to be deposited into a trust fund operated by the Cincinnati Southern Railway Board of Trustees, with the City of Cincinnati as the sole beneficiary, the moneys to be annually disbursed to the municipal corporation in an amount no less than $26,500,000 per year, for the purpose of the rehabilitation, modernization, or replacement of existing streets, bridges, municipal buildings, parks and green spaces, site improvements, recreation facilities, improvements for parking purposes, and any other public facilities owned by the City of Cincinnati, and to pay for the costs of administering the trust fund?”

A YES vote supports the proposed sale.

A NO vote opposes the proposed sale.

7. Has anyone tried to buy the CSR before?

Yes. In 1896, the Southwestern Construction Company attempted to buy the CSR even though it was under lease to the CNOTP.

Voters defeated the sale by just 338 votes out of 31,324 votes cast.

Norfolk Southern wanted to buy the Cincinnati Southern Railway in 2009, offering $500 million. City officials at the time were immediately skeptical.

“When I was mayor, the CEO of Norfolk Southern came into my office to see me and offered half a billion dollars for the railroad. That to me wasn't real money,” said then-Mayor Mark Mallory at a recent press conference. “I have been traditionally not in favor of selling the railroad because I didn't think the railroads would ever bring a figure that came close to the value of our railroad. But the experts that we hired let us know that the value of our railroad was matched in the offer that Norfolk Southern gave us of $1.6 billion.”

The CSR Board never seriously negotiated with Norfolk Southern and a sale didn’t even get close to being put before voters.

8. Could the CSR be used for passenger rail, at least in theory?

Yes, railroad tracks are the same for passenger and freight cars — a “conversion” would just mean using different train cars on the tracks.

Amtrak currently operates out of Cincinnati, traveling northwest to Chicago and southeast to Charlottesville, Va. A plan to expand Amtrak service includes going north from Cincinnati to Dayton, Columbus, and Cleveland; Amtrak does not plan to expand service south through Kentucky and Tennessee.

Amtrak selected areas for expansion based on “population megaregions” predicted to have the greatest ridership demand based on population size, economic activity, transit connections, existing travel markets and urban density (according to the 2021 report “Amtrak Connects US: More Trains. More Cities. Better Service.”)

Under the existing lease, CNOTP would need to consent to any third parties sharing the line.

9. What regulatory control does Cincinnati have over the CSR/Norfolk Southern right now? What regulatory control would the city have after a sale?

Railroads in the United States are regulated at the federal level by the Federal Railroad Administration, which is part of the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Municipalities do not have regulatory control over things like what is transported, how it is transported or labeled, or train speeds. So, the city has no regulatory control over Norfolk Southern’s operations on the Cincinnati Southern Railway.

10. How much money does Cincinnati get per year under the current lease? Who decides how it’s spent?

Cincinnati gets around $26 million a year from Norfolk Southern under the terms of the current lease. The amount is determined by the lease with an increase each year using a calculation based on the Implicit Price Deflator for Gross National Product (developed by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis).

The current lease expires in 2026, but Norfolk Southern chose to exercise their right to extend the lease another 25 years through 2051. However, the annual rent starting in calendar year 2027 would have to be negotiated.

The CSR Board started that negotiation in December 2020, requesting Norfolk Southern start paying $65 million a year (increasing gradually in the same way it does now). Instead, Norfolk Southern responded with an offer to buy the railway for $865 million. The board’s response, through a hired firm, was, “the compensation offered is grossly inadequate.” After months of back and forth, the highest annual lease Norfolk Southern offered started at $37.3 million a year.

Since 1987, the city has used all lease revenue for infrastructure projects; that policy was established by City Council. Infrastructure spending is within the city’s capital budget (rather than the operating budget, which covers city services like police). Lease revenue makes up about 40% of the city’s capital budget and is the largest single source of revenue for the capital budget.

City Council has final say over all budget allocations. The capital budget is established along with the biennial operating budget every two years.

11. How much money would Norfolk Southern pay the city for the CSR? What would be done with that money?

Norfolk Southern would pay the city $1.6 billion in a single lump sum payment. That price was negotiated between Norfolk Southern and the CSR Board of Trustees.

The Cincinnati Southern Railway Board of Trustees would put the entire amount in a trust fund; a third-party will decide how to invest it, with a goal of growing the principal with interest from the investments.

The sale agreement also includes $5 million in an Accelerated Transaction Fee, plus up to $20 million in a transaction extension fee because Norfolk Southern requested a delay in closing until March 2024.

12. Who negotiated the sale price and how did they reach $1.6 billion?

The current lease expires in 2026, but Norfolk Southern chose to exercise their right to extend the lease another 25 years through 2051. However, The annual rent starting in calendar year 2027 would have to be negotiated.

The CSR Board started negotiations in December 2020 with an offer to increase yearly rent from about $25 million a year to $65 million a year, increasing annually with inflation. Norfolk Southern responded in July 2021, offering to buy the railway for $865 million, plus $50 million paid over a period of one to four years. Norfolk Southern didn't respond to the board's proposed lease terms.

"[T]hese proposals, in departing from the current leasing framework, provide the CSR an additional benefit — a hedge against any sort of rail industry structural decline," wrote Norfolk Southern VP Mike McClellan in a letter to the Board.

The board refused the offer, calling it "grossly inadequate" and again offering the $65 million a year lease.

Norfolk Southern then upped their offer to $915 million, plus up to $50 million depending on how quickly the sale could be finalized, and again ignored the attempt at negotiating a new lease amount.

The board responded with a $2 billion sale offer, or the continued offer of a $65 million a year lease. Norfolk Southern's next offer in November 2021 was just over $1 billion, which the board countered with a $1.8 billion offer plus up to $50 million more depending on how quickly the deal was finalized.

The final Norfolk Southern offer in April 2022 was for $1.55 billion plus up to $50 million more depending on how quickly the deal was finalized, and a lease offer increased to $37.3 million annually, the highest Norfolk Southern offered for the yearly lease during the entire negotiation.

This is where key deadlines started to put pressure on the negotiations — if no agreement was reached by June 30, 2022, the existing lease says the parties have to enter into arbitration.

"That arbitration clause introduces so much risk and uncertainty," Mayor Pureval said. "Because the arbitrator could choose any one of these valuations, irrespective of our opinion."

"I think we all believed that we had pushed as far as we were going to get," Muething said, "and if we didn't take that $1.6 billion we were gonna start this [arbitration] process, and then we didn't know where we're going to end up."

13. How much money would the city get per year after the sale? How is that amount estimated?

The lowest amount the city would get each year is $26.5 million to start unless the principal amount falls below a certain threshold (explained further below). That $26.5 million minimum would increase annually using the same calculation that determines the yearly increase in lease payments, which is based on the Implicit Price Deflator for Gross National Product (developed by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis).

The CSR Board of Trustees intends to give the city more than the minimum amount each year, and that number is likely to vary depending on market conditions.

The board hired two consulting firms to estimate how much money could be earned from investment returns. After deducting an unknown amount to be added to the principal each year, and an unknown amount needed for CSR operations, the consultants say the city can expect $57.1 million a year.

That estimate is based on a 5.5% annual net return and 2% inflation, generating a 3.5% real return. The amount is projected to grow each year, reaching an estimated $131.2 million in 2066 (in 2024 dollars). Officials say that is a conservative estimate based on current market conditions.

Because of the minimum payment clause, there could be a time when the CSR Board dips into the principal (the original $1.6 billion) instead of paying from investment returns.

When Ohio lawmakers changed state law to allow the sale to proceed, they included a “safeguard” in case there are several years of negative investment returns. If the principal amount ever decreases by 25% or more in a single year, payments to the city must be suspended until the fund reaches the previous level.

14. Who would decide how the sale revenue is invested?

The Board of Trustees plans to hire an investment advisor and an investment manager. A request for proposals for an investment advisor was active until Sept. 29.

According to the RFP, the chosen investment partner will “provide initial recommendations to the Board and then act upon such policies and procedures approved by the CSR Board by balancing the investments in the portfolio and engaging with any investment managers retained by the CSR Board.” The RFP specifies that the investment partner will not be allowed to invest money from the CSR Trust into any of its own products.

The CSR Board is looking for “simplicity in the investment strategy and low risk.” The advisor will also help the CSR Board choose an investment manager.

WVXU asked the mayor and a few council members if council would have any oversight over what the infrastructure fund is invested in.

“It's council's prerogative to set the guidelines and the principles upon which the Cincinnati railroad board will act from an investment perspective,” Mayor Pureval said. “We will make every effort to get community input to identify our priorities, values and principles, and communicate that effectively and clearly to the railroad board.”

Councilmember Meeka Owens, chair of the Climate, Environment, and Infrastructure Committee, said investments should follow council’s priorities.

“It will be our prerogative to make sure we are aligning ourselves with those priorities in how we invest these dollars,” Owens said.

Several years ago, Cincinnati City Council asked the pension fund’s Board of Trustees to divest from private prisons. The Board refused, saying it would be bad for the financial health of the fund.

15. Who would decide how the investment income is spent?

State law mandates how the money can be spent. Any changes to that would require a change in state law (passage in both the Ohio House and Senate, with final approval from the governor).

The CSR Board established rules for how investment income can be spent. The negotiated sale agreement made the sale contingent on passage of a state law that would allow the creation of a trust fund with certain requirements: Proceeds from the fund could only be spent on "rehabilitation, modernization, or replacement of existing infrastructure improvements" and could not be used to construct new infrastructure improvements.

When state lawmakers took up the issue earlier this year, they expanded on that requirement to make it even more specific: “…for the purpose of the rehabilitation, modernization, or replacement of existing streets, bridges, municipal buildings, parks and green spaces, site improvements, recreation facilities, improvements for parking purposes, and any other public facilities owned by the City of Cincinnati, and to pay for the costs of administering the trust fund.”

That includes street paving and pothole repair, recreation centers, public parks, etc.

In response to a request from City Council, the City Manager’s Office put together a plan for how the money could be spent. The report estimates investment revenue over the next ten years would be at $250 million more than if the city continued the lease; that amount is broken down into specific departments and projects:

- Parks - $40.7 million

- Recreation - $27.6 million

- Streets and sidewalks (transportation infrastructure) - $101 million

- Public services (including police and fire) - $49.6 million

- Health - $31.1 million

See a full list of specific projects in the report below:

As with all city spending, City Council has the final say; in this case, that means which infrastructure projects to fund with the money restricted to that purpose. The budget process each year starts with the city manager’s office (typically in close collaboration with the mayor’s office), and City Council can make changes before voting on final approval.

LEARN MORE: How Cincinnati could spend the money from a potential Cincinnati Southern Railway sale

It’s not yet clear how much will be needed to administer the trust fund. Members of the Board of Trustees do not receive compensation.

16. How much is the Cincinnati Southern Railway worth?

The CSR Board of Trustees paid for two separate valuations to determine what the railway is worth. The range is wide: $616 million on the lowest end and $2.46 billion on the highest.

One way to estimate value is to calculate how much it would cost Norfolk Southern to move rail traffic using a different route, known as the "next best alternative." This was hard to calculate because Norfolk Southern refused to give the consultants all the necessary financial information.

"They claimed that they didn't keep financial information on a segment basis just for this segment from Cincinnati to Chattanooga," said CSR Board President Paul Muething.

Another method is to estimate how much the CSR would be worth to a different third-party buyer, and this is where some of the lowest valuations come from. Muething says that includes two different kinds of potential buyers: financial and strategic.

"Financial would be some sort of fund or something that would buy this asset just to own it," Muething said. "Well, the problem with a financial buyer is the financial buyer would still have to deal with [Norfolk Southern] as its lessee."

A strategic buyer, on the other hand, would be one of four or five other major rail lines, which are already moving traffic north to south and south to north on other rail lines.

To learn more, WVXU again spoke to FreightWaves Senior Staff Reporter Joanna Marsh.

“[The CSR] begins and ends on Norfolk Southern’s network, and so then you'd have to work with NS in terms of trackage rights and that kind of thing,” she said. “You'd have to make a business case to have an open sale and I'm not sure the business is there.”

Another rail company purchasing the line would require closer scrutiny from the federal Surface Transportation Board, which reviews each sale "to make certain that it does not substantially lessen competition, create a monopoly, or restrain trade, and that any anticompetitive effects are outweighed by the public interest."

A third valuation method is based on Norfolk Southern's 2009 offer to buy the CSR for $500 million. Muething wasn't on the CSR board at the time, but he calls it a "half-hearted" purchase attempt.

Adjusted for inflation, that same offer would be worth between $616 million and $683 million today. But using the Surface Transportation Board's estimated increase in value since 2009, that offer would be worth up to $1.55 billion today.

Finally, an opportunity cost estimates how much money Norfolk Southern could lose in profit if they lose access to the CSR. That range has the most variability, between $1.11 billion and $2.4 billion.

17. What kind of government oversight is required for the sale to go through?

It’s often said that Ohio lawmakers had to change state law to allow the CSR Board to sell the railway. Actually, the board could have put a sale to voters without a state law change, but they wanted to change the way they could spend the revenue from a sale.

The Ferguson Act of 1869 is the state law that originally authorized Cincinnati to build the railway. It was necessary because a provision in the Ohio Constitution of 1851 prohibited counties, cities and towns from becoming owners in any joint stock company, meaning the city couldn’t loan money to a private company to build a railroad.

A later amendment to the Ferguson Act said that if the city ever sold the railway, the revenue could only be used to pay off debt service. (Note: the city retained debt to pay for initial construction but paid that off decades ago).

The CSR Board went to state lawmakers because they wanted to use the revenue for city infrastructure and needed the state law change to make that possible. The change allows the revenue from a sale to be put in a “trust fund for the purpose of receiving the net proceeds of the sale.” The revised Ferguson Act stipulates how the trust fund would be managed, including prohibiting any member of the CSR Board of Trustees from having “any direct or indirect interest in the gains or profits of any investment made by the railway board of trustees.”

When lawmakers approved the requested changes, they added several other things to regulate the sale:

- Allowing the sale to go on the ballot only once in 2023 or 2024. If it fails, state lawmakers would need to approve another attempt.

- If the principal amount of the investment account decreases by 25% or more, payments to the city must be suspended until the fund reaches the previous level.

- The ballot language must include the name of the buyer's parent company — in this case, Norfolk Southern.

The federal Surface Transportation Board reviews each sale "to make certain that it does not substantially lessen competition, create a monopoly, or restrain trade, and that any anticompetitive effects are outweighed by the public interest."

The STB is an independent federal agency which “exercises its statutory authority and resolves disputes in support of an efficient, competitive, and economically viable surface transportation network that meets the needs of its users.”

The STB decided Sept. 20 that the sale of the CSR to Norfolk Southern does not have any anticompetitive effects. In the same decision, the STB approved an agreement that allows CNOTP to continue operating on the line once the sale is complete (if voters approve).

18. Would the city lower taxes if the sale is approved? Or promise not to raise taxes?

That’s unlikely. City officials expect a significant deficit in future budgets due to declining income tax. Additional revenue from the sale of the CSR wouldn’t fully solve the city’s deferred maintenance problem or overall budget concerns.

There are two property taxes for the city: one goes directly into the city’s General Fund in the Operating Budget, so it doesn’t affect how much the city spends on maintaining current infrastructure. There’s a separate debt service millage within the Capital Budget that supports payments on debt used for capital expenditures (which can include maintenance but can also include new infrastructure).

The city’s income tax primarily goes to the Operating Budget.

WVXU asked Mayor Pureval if he promised not to raise taxes if the sale is approved.

"Whenever I talk about taxes, I'm very specific to say no new taxes on the capital side,” Pureval said. "We impaneled the Futures Commission to do a deep dive on our revenues and our expenses, to give us recommendations on what we need to do in order to have more of a fiscally sound budget. Now, everything's on the table from that perspective, including potentially raising taxes."

19. Could the city sell the CSR to another railroad company? Or to anyone for another purpose?

Technically, yes. However, Norfolk Southern could retain control over the operation until 2051. Officials say that makes it very unlikely any other company would be interested, for any purpose.

“[The CSR] begins and ends on Norfolk Southern’s network, and so then you'd have to work with NS in terms of trackage rights and that kind of thing,” said Marsh of FreightWaves. “You'd have to make a business case to have an open sale and I'm not sure the business is there.”

Another rail company purchasing the line would require closer scrutiny from the federal Surface Transportation Board, which reviews each sale "to make certain that it does not substantially lessen competition, create a monopoly, or restrain trade, and that any anticompetitive effects are outweighed by the public interest."

The STB decided Sept. 20 that the sale of the CSR to Norfolk Southern does not have any anticompetitive effects. In the same decision, the STB approved an agreement that allows CNOTP to continue operating on the line once the sale is complete (if voters approve).

20. What happens if the sale proposal fails?

Ohio lawmakers limited the city to one attempt to sell the CSR. That means if the Board of Trustees wants to try again in another election, they’ll have to get permission from state lawmakers again first.

The sale agreement passed by the CSR Board states that if voters reject the sale, either party can terminate the sale agreement within 30 days after the vote is certified.

If the CSR Board and/or Norfolk Southern choose to terminate the sale, the parties will likely re-open negotiations for the remainder of the lease (through 2051).

If neither party terminates, they will instead work together to lobby state lawmakers to allow another attempt on the ballot.

21. Who is funding the campaign in favor of approving the sale?

A campaign in favor of approving the sale, Building Cincinnati’s Future, is funded by “Build Cincinnati's Future,” a political action committee formed and initially funded by Norfolk Southern.

The campaign is run by Jens Sutmoller of JS Strategies, which specializes in ballot measures. Sutmoller is also working on campaigns in favor of Issue 19 (the Hamilton County tax levy for the Cincinnati Zoo) and Issue 20 (the Hamilton County tax levy for the public library system).

Sutmoller told WVXU in July the campaign hoped to accept donations to the PAC from entities and individuals other than Norfolk Southern. The first campaign finance report, however, shows Norfolk Southern is the only funder so far.

The company has put in $4,250,000 and spent $4,201,827.31. That covers the period from when the PAC was formed on July 14 through Oct. 18.

Norfolk Southern initially deposited $2 million into the PAC on July 21, then added another $1.5 million on August 15, then a third contribution of $750,000 on Oct. 16. Expenditures so far include consulting and research, with most of the money going toward ad buys. Mayor Aftab Pureval appeared in some television and online video ads but was not paid for that work.

The city charter prohibits spending public money for political activity. That means public officials can’t use their official position to advocate for or oppose the sale; that includes elected officials, non-elected officials like city administration, and the CSR Board of Trustees. However, any of those people can act as individuals in support or opposition; they can also donate to a PAC but are subject to the same donation limits as all other individuals (no more than $15,499.69 to a single political action committee per calendar year).

PACs are not subject to campaign finance reporting for the city of Cincinnati or the Federal Election Commission. The first campaign finance report required by Ohio is due Oct. 26, to disclose activity through Oct. 18. The next campaign finance report required by Ohio is due Dec. 15 for activity through Dec. 8, and Jan. 31 for activity through Dec. 31.

22. Who is funding the campaign opposed to the sale?

Three political action committees opposing Issue 22 have been filed:

- Citizens for a Transparent Railroad Vote

- Stay on Track

- Save Our Rail

The three PACs combined have raised less than $5,000 and spent about $1,500.

Save Our Rail, Treasurer Shawn Baker: raised $4,859.48, spent $1,493 (plus a $5,000 in-kind contribution from “Reversed Out LLC” for a website). Donors are 14 individuals (including former Mayor Dwight Tillery and former Council Member Kevin Flynn), one LLC (City Lands Development Co LLC), and one candidate campaign (Citizens for Bauman).

Stay on Track, Treasurer Sil Watkins: raised $100, spent $0 (plus a $1,105 in-kind donation for printing).

Citizens for a Transparent Railroad Vote did not file a campaign finance report; a report is not required if the PAC has not spent or raised at least $1,000.

PACs are not subject to campaign finance reporting for the city of Cincinnati or the Federal Election Commission. The first campaign finance report required by Ohio is due Oct. 26, to disclose activity through Oct. 18. The next campaign finance report required by Ohio is due Dec. 15 for activity through Dec. 8, and Jan. 31 for activity through Dec. 31.

23. What are the arguments against selling the Cincinnati Southern Railway?

Some critics, like former Council Members Kevin Flynn and Christopher Smitherman, say it’s foolish to sell an asset that has brought the city steady revenue for over a century.

Some say the negotiated sale price is far lower than the railroad is worth, and that the CSR board could convince Norfolk Southern to pay a much higher annual lease. This includes the Charter Committee of Greater Cincinnati: “Our review shows the valuation of $1.6B is too low and hence the lease value will be higher than quoted,” the committee said in a statement. “We are also concerned that the ‘guardrails’ crafted by the Ohio General Assembly are insufficient to prevent future shenanigans by elected officials. We find the lack of transparency of the proposed deal and its negotiations troubling.”

Some are opposed to selling any public asset to any private company, including Railroad Workers United, a North American “inter-union, cross-craft solidarity caucus of railroad workers.” The group advocates for public ownership of all railroads. “The large rail systems in the United States — which includes Norfolk Southern and five others — have become more and more concentrated in recent decades, while running roughshod over rail workers, passengers, shippers and communities along their routes,” says a July 17 news release. RWU International Steering Committee Member Michael Paul Lindsey wrote an op-ed in the Enquirer as well.

Some are opposed to selling to Norfolk Southern specifically, fueled by the derailment of a Norfolk Southern freight train carrying hazardous materials in East Palestine, Ohio earlier this year.

A group of Cincinnati residents is working together under the slogan “Derail the Sale.” Abby Friend and Jen Mendoza, both Northside residents, are two of the organizers. They describe the effort as a “nonpartisan coalition of community members.”

RELATED: Cincinnati Council joins other leaders in asking for stronger railroad safety regulations

“We see it as a means to preserve opportunities for future transportation development across the region, as well as an immediate and lasting effort to protect workers, taxpayers, our communities, our ecosystems,” Friend told WVXU. “We feel it's really important to stand against a corporation who refuses over and over and over again to be held accountable for their negligence.”

As described above, a “Save Our Rails PAC” was formed in September by “a broad coalition of Cincinnatians opposed to the sale.”

Some critics are not necessarily opposed to selling the Cincinnati Southern Railway, but say the revenue should not be spent on maintaining infrastructure.

That conversation started back in February in an op-ed authored by Damon Lynch III, Iris Roley, and Al Gerhardstein, which says the sale should not go forward unless much of the revenue from the trust fund is dedicated to “repairing harms from racist city policies that destroyed generational wealth for thousands of Black families in Cincinnati.”

They write that money from the lease over the last century “promoted racial discrimination” in many ways: “The money helped build and maintain the [city’s first] streetcar system which allowed whites to move to the first-ring suburbs in the early 1900s. Other infrastructure projects funded in part by the railroad and hurting Black residents included interstate highways and segregated public housing units. These policies combined with redlining, overt race discrimination in house sales and renting, the exclusion of Blacks from federal loan programs, and other discriminatory policies to prevent Blacks from creating generational wealth.”

RELATED: Cincinnati officials release 'blueprint' for ending the city's racial wealth gap

Lynch and Roley held a meeting Oct. 1 to organize opposition to the sale.

"Right now our vote is no — no, we do not support the sale," Lynch told a crowd of about 85 people. "Our interest was not considered. And the way this deal is structured does not support the closing of the racial wealth gap that the city says it wants to close ... The people who negotiated on the city's behalf had no thought about negotiating on our behalf. It depends, it matters, who you put in the room."

Lynch criticized a lack of community engagement on the proposed sale; no public meetings hosted by the mayor, city administration, City Council, or Norfolk Southern.

"Early voting starts October 11 — it's late, the train is coming down the track. And as usual either we're on the caboose or we're getting run over," Lynch said. "Our goal is that the same way the city has a pot of money — that they're taking the interest and they're doing whatever — is that Black folk have a pot, a development fund that is controlled by us ... and we go in and we start to build and develop our own community."

The NAACP announced Oct. 11 their opposition to the sale, joined at a press conference by Lynch and Roley.

Cincinnati NAACP President Joe Mallory says the lack of public engagement on the plan is concerning.

"We're not the monolith for the entire Black community, but we do have a constituency that we represent," Mallory said. "We're tired of being left behind and forgotten. We deserve a seat at the table, not as an afterthought ... we need to be [there] from the beginning with a racial equity lens."

Council Member Scotty Johnson was the only council member to vote no when it came time to put the measure on the ballot. (Note: That vote was a technicality; council could not have blocked the proposal from the ballot.) Johnson explained his vote at the opposition meeting.

"The reason why is because there was nothing in place that was going to trickle down to our community ... we must see considerable change in the Black community with the sale of the railroad," he said. "This is your city. And make sure you stand firm ... Stand strong. You do have help at City Hall."

Vice Mayor Jan-Michele Lemon Kearney, who previously expressed enthusiastic support for the sale, also attended the meeting. She told WVXU Oct. 1 she always expected equity from the sale, but now agrees that equity needs to be in writing. Kearney says she and Johnson are working on an ordinance to that effect.

The sale as it will appear on the ballot does not allow for spending even part of the revenue on anything except maintaining current infrastructure. Lynch says that's why voters should kill the sale.

"Norfolk Southern — they want the railroad. Ain't like they going anywhere, they'll renew the lease," Lynch said. "But this time before you have any kind of sale, you got to come talk to us."

24. Why do city residents get to decide whether the railway is sold?

City residents have to approve the sale because that is a requirement of state law. The Ferguson Act was first passed by the Ohio Legislature in 1869, and allowed the city of Cincinnati to borrow money for the purpose of building a railway, but only if a majority of city voters approved. The Ferguson Act was later updated to allow the city to sell the railway, but only if a majority of city voters approved.

25. If the sale goes through, how would the city's overall budget be affected?

The City Manager’s Office does not expect additional revenue from the sale to alleviate significant deficits projected in the operating budget over the next several years. Officials are predicting a $9.4 million deficit for fiscal year 2025, even after using the $25.2 million left from ARPA; it will be the last fiscal year with pandemic stimulus funds.

“I want to be very clear that the CSR sale is not expected to have material impacts on the city's operating budget, especially in the short term,” said Assistant City Manager Billy Webber at a recent council meeting. “There is the potential for some long term savings derived from capital investment, but they will be derived over longer periods of time.”

The operating budget includes the services provided by the city, like police officer patrols, trash collection and operating the water treatment system. It includes wages for city employees and the cost of supplies needed to deliver services. The operating budget includes the General Fund, where City Council has the most flexibility in funding decisions.

LEARN MORE: How to understand the city budget

The capital budget covers purchasing or improving city assets like buildings and vehicles. It includes assets that cost at least $10,000 and last at least five years.

General Fund dollars can be used for capital projects, but capital dollars cannot be used for operating. For example, some salaries were moved from the General Fund to the Capital Budget when the city started experiencing deficits. If the Capital Budget eventually has enough revenue to adequately maintain infrastructure, those salaries could be moved back to the General Fund.

Additional revenue from the sale IS expected to result in some savings within the Capital Budget.

“This increase in funding for existing infrastructure will provide additional flexibility in those other general capital resources, primarily income tax and property tax,” Webber told council. “The administration has made a proposal that if the sale is approved, at minimum, $3 million per year in those other capital resources would be committed to community and economic development projects.”

26. Will the CSR Board of Trustees get a bonus payment, or any kind of payment, if the sale goes through?

No. Nothing in the sale agreement allows for bonus or other personal financial payments to members of the CSR Board of Trustees. The board members also do not receive payment for serving on the board.

27. Did enslaved people build the Cincinnati Southern Railway?

No. It’s true much of the rail in the southern U.S. was constructed using the forced labor of enslaved African Americans. Railroad companies documented their purchases of people for the purpose of slave labor.

“Railroads began buying hundreds of male slaves between the ages of 16 and 35 as early as 1841, and in the 1850s were either renting or buying 'hands' in groups of hundreds,” says a research project from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Construction on the Cincinnati Southern Railway started in the early 1870s, about 10 years after the Emancipation Proclamation and about eight years after the last Confederate community of enslaved Americans in Galveston, Texas, received word that they had been freed (what’s now known as Juneteenth).

Early construction on the CSR, however, did use forced labor of convicts.

“While many believe that the 13th Amendment ended slavery, there was an exemption that was used to create a prison convict leasing system of involuntary servitude to fill the labor supply shortage in the southern states after the Civil War,” writes Lynn Weinstein for the Library of Congress. “Black Codes regulated the lives of African Americans and justice-involved individuals were often convicted of petty crimes, like walking on the grass, vagrancy, and stealing food. Arrests were often made by professional crime hunters who were paid for each ‘criminal’ arrested, and apprehensions often escalated during times of increased labor needs.”

An article in the Cincinnati Enquirer published November 14, 1874, documents one example of convict labor used to construct the Cincinnati Southern Railway. The author describes difficulty retaining contractors and workers for a particular stretch of the railway in Tennessee. One contractor hired “something like a hundred of the squirrel-hunters from the neighboring hillsides and valleys” before abandoning the project entirely, “sturdily cursing the Southern Railroad and vowing they’d enough of it.”

Two contractors – Cherry O’Conner & Co., of Nashville, and W.H. Cox, of Cincinnati – are said to employ convict labor from the Tennessee Penitentiary.

“The fellows in stripes – zebras I heard them called more than once – numbering about three hundred in all, can be depended upon with more certainty than other hands, for two reasons: Pay-day doesn’t come around to them, and they can’t get drunk,” the Enquirer article states. “But it is not a very pleasant thing to see them at work with the guard sitting around with their long fowling-pieces, and know that with a leader they, the stupid fellows, could in a moment rise and slaughter everything before them. There was no fun at the headquarters, either when they were marched in to dinner and the guards marched up and down with their guns on their shoulders, afraid to give them the least chance to gain their liberty.”

According to the article, up to a dozen of the convicts attempted to escape, and five succeeded; two others were shot, one fatally, and the rest were recaptured.

Four years later, the lead contractor Huston & Co. told the Cincinnati Southern Railway Board of Trustees they would not use convict labor during construction. A letter from Huston & Co. President Miles Greenwood to the CSR Board was published in the Enquirer on August 3, 1878:

“Gentlemen: As there has been considerable discussion, both public and private, upon the probability of our using convict labor to complete the Cincinnati Southern Railway, in case the contract for its completion should be given to us, we desire to say to you, and through you to the public, that we will not use convict labor on the work of completing the Cincinnati Southern Railway. Under the laws of Kentucky convict labor can not be used on work of public improvement. In Tennessee the use of such labor is allowable, but in neither State is such labor desirable upon such work as will be required in the completion of the Cincinnati Southern Railway. Very much the largest portion of the work will require skilled labor, which convict labor is not. Besides this, we believe the work can be more expeditiously and profitably finished by free labor and for these reasons we will use free labor altogether.”

The final rail was spiked into place a little over a year later, on December 10, 1879.

28. Is the city currently liable for wrecks involving Norfolk Southern that happen on the Cincinnati Southern Railway?

The current lease was last updated in 1987 and expires in 2026, except that Norfolk Southern has exercised its right to extend the lease through 2051. The agreement includes this clause:

- During the term(s) hereby granted Lessee [Norfolk Southern] will pay and save harmless the Lessor [city of Cincinnati] from the payment of any costs, expenses, claims, liabilities, damages and demands whatsoever arising out of the Lessee’s possession, control, management and operation of the said line of railway and its equipment, or any part of the leased premises. Lessee assumes the duties, liabilities and obligations of an owner, doing every act and thing required by law of the Trustees, their successors or assigns. If Lessee shall be covered by insurance for any of its obligations set forth in this Section 4, it will, if it can do so without added premium cost, name Lessor as an additional insured. During the term(s) hereby granted Lessee also shall provide to Lessor an annual report summarizing the condition of the leased premises, the nature of repairs or replacements made with respect thereto, and the sale of any rail lines between Cincinnati, Ohio and Chattanooga, Tennessee during the previous twelve months.

City Attorney Kaitlyn Geiger discussed this provision during a presentation to City Council in February: “If there was an incident on our line, Norfolk Southern is required to hold us harmless for that and to indemnify us,” she said. “If there's a lawsuit that would include any attorneys fees, any settlements or judgments, those types of things, that would be Norfolk Southern costs and not the city's or the boards’.”

When the topic came up again during a meeting on Oct. 3, Deputy City Solicitor Marion Haynes seemed to have a different perspective.

“As the owner of the rail currently, the city is exposed to the potential for liability as the owner of the property,” Haynes told a council committee. “In the event of an adverse environmental event, it's very likely that the city would be drawn into litigation. And while there is an indemnity in our lease … with such large exposure, almost without doubt the city would incur some kinds of costs, if not ultimately, damages in association with them.”

When asked about the seemingly contradictory statements, a city spokesperson provided this statement:

“We do not consider the two statements to be in conflict, and we believe there are scenarios in which the City and/or the CSR Board could be subjected to liability for wrecks involving Norfolk Southern that happen on the Cincinnati Southern Railway. As Attorney Geiger noted, Norfolk Southern is contractually required to indemnify the City and the CSR Board from claims and damages resulting from Norfolk Southern’s activities on the railway. However, as Attorney Haynes recognized, the City and the CSR Board would likely be included in litigation resulting from an East Palestine-type event by virtue of their interest in the railway. And though the City’s lease and purchase agreement with Norfolk Southern contain indemnity provisions that mitigate the City and Board’s exposure, those protections are only as good as Norfolk Southern’s financial position. So, there are scenarios (e.g., a Norfolk Southern bankruptcy following an environmental disaster) in which those protections may not be available to the City and the CSR Board. Further, there are environmental laws (e.g., the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act) that can impose strict liability on the owners of contaminated properties regardless of fault. And the long-term impacts of an event such as the one in East Palestine may not be known for years, even decades, making it impossible to know or predict the associated costs. Finally, there is always the risk of litigation between the City/CSR Board and NS over the application of the indemnity protections, especially if the amount in controversy is significant. Thus, while the City and the CSR Board should be held harmless for wrecks on the railway, we cannot absolutely rule out that the City and the Board will not incur costs and expenses due to those wrecks.”

29. What guidelines are in place to prevent abuse of the trust through high overhead costs?

State law requires the CSR Board of Trustees to retain at least one independent financial advisor. The board may also “retain managers, administrative staff, agents, attorneys, and employees, and engage advisors, as are appropriate and reasonable in relation to the assets of the trust fund, the purposes of the trust, and the skills and knowledge of the members of the railway board of trustees, in order to fulfill the board’s duties and responsibilities in administering the trust fund.”

Paying those advisors and “other reasonable expenses of administering the trust fund” would come from the investment earnings. There is no stipulation on a maximum number of advisors or administrative staff. Board members themselves do not receive payment.

The board must submit audited financial statements to the city’s finance director every year. The board must also consult with the finance director on management and investment policies.

The board must establish these management and investment policies “to ensure the trust fund is administered efficiently and self-sustaining, and that the money and assets in the trust fund are not diminished while providing the municipal corporation payments…” The policies must address:

- Asset allocation targets and ranges

- Risk factors

- Asset class benchmarks

- Eligible investments

- Time horizons

- Total return objectives

- A strategy for long-term growth of the principal of the trust fund

- Competitive procurement processes

- Fees and administrative expenses

- Performance evaluation guidelines

The final management and investment policies must be made public.

The board is required by Ohio law to follow the “prudent investor standard of care,” which includes:

- A trustee shall make a reasonable effort to verify facts relevant to the investment and management of trust assets

- A trustee’s investment and management decisions respecting individual trust assets shall not be evaluated in isolation but in the context of the trust portfolio as a whole and as part of an overall investment strategy having risk and return objectives reasonably suited to the trust.

- Trustee shall consider these circumstances: the general economic conditions; the possible effect of inflation or deflation; the expected tax consequences of investment decisions or strategies; the role that each investment course of action plays within the overall trust portfolio, which may include financial assets, interests in closely held enterprises, tangible and intangible personal property, and real property; the expected total return from income and appreciation of capital; other resources of the beneficiaries; needs for liquidity, regularity of income, and preservation or appreciation of capital; an asset’s special relationship or special value, if any, to the purposes of the trust or to one or more of the beneficiaries.

30. If the railway is sold, will any money be used to pay for upkeep of Paycor Stadium, Great American Ball Park, TQL Stadium, or any future stadiums?

No. If the railway is sold, funds would be restricted to maintaining current city-owned infrastructure.

TQL stadium is owned by The Port of Greater Cincinnati. Paycor Stadium and Great American Ball Park are owned by Hamilton County, so public dollars are used for upkeep (and possibly even expansion/improvements), but that’s all done through the Hamilton County budget (specifically sales tax). The proceeds of a railway sale could NOT be used for upkeep of any current stadiums.

The same answer is true for future stadiums or arenas, or really any infrastructure. The money can’t be used to build anything new. Eventually though, a new bike path built with other public money, for example, would become “current infrastructure” and would be eligible for funding from the railway trust. But any infrastructure would have to be owned by the city to be eligible. There’s no proposal right now for the city to own a future stadium or arena, and it’s a pretty unlikely scenario.

31. What happens to the current CSR Board of Trustees if the sale goes through?

If voters approve the sale, the existing Board of Trustees will continue; instead of managing the Cincinnati Southern Railway, the board would “manage and administer the railway proceeds trust fund.”

The board would continue to operate under the current structure: five members, each appointed by the mayor of Cincinnati and approved by a majority vote of city council. Terms are five years and there are no term limits. There is no compensation for serving on the board. No more than three members may be of the same political party at any time.

One new requirement, per the state law change enacted over the summer, is that new board members must reside in the city of Cincinnati.

Learn more in Question 4 and Question 14.

32. Would any portion of the purchase price, or any funds disbursed from the trust fund, be subject to state or federal tax?

No.

33. Who would pay the closing costs?

Norfolk Southern is responsible for paying all closing costs except for the city’s attorney’s fees. That includes costs associated with regulatory approvals, recording costs, deed taxes, sales taxes, title company costs and transfer taxes.

34. How much land does the city own along the entire Cincinnati Southern Railway?

The property includes about 9,500 acres of land total along the roughly 337-mile railway between Cincinnati and Chattanooga, Tenn. The sale agreement includes all of that property.

Norfolk Southern paid for a market valuation of the property on which the railway sits; those documents were released by the CSR Board as part of a public records request this summer. The valuation determined some segments of the line are as narrow as 22-feet wide, with other sections nearly 1,500-feet wide. The average width is between 167 feet (for the section between Cincinnati and Danville, Ky.) and 187 feet (for the section between Danville and Chattanooga). Some portions of the rail line are a single track, while others contain two tracks side-by-side. The property has a variety of zoning designations including residential, agricultural, commercial, forest, mixed, and some with no zoning designation.

With a number of caveats and limiting factors, the valuation was determined to be between $120 million and $257 million; this includes only the estimated market value of the land itself, not any improvements on the land (i.e., not the railway).

This valuation includes about 333 miles of the rail line, a total of about 7,500 acres. It does not include any spurs associated with the line (meaning small sections of rail that split from the main line).

SOURCES:

- Documents related to the proposed sale, including the full agreement, are available on the Cincinnati Southern Railway Board of Trustees website

- The Cincinnati Southern Railway Board of Trustees website

- Archived editions of the Cincinnati Enquirer

- Butler, Tod Jordan. “The Cincinnati Southern Railway: A City’s Response to Relative Commercial Decline” The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971

- Pamphlets, newspaper clippings, maps, fliers, and other documents from the Cincinnati History Library and Archives at the Cincinnati Museum Center

- Documents obtained through public records requests from the City of Cincinnati and the CSR Board of Trustees

- Public meetings and press conferences

- The Library of Congress

- Marsh, Joanna, FreightWaves Senior Staff Reporter